Table of Contents

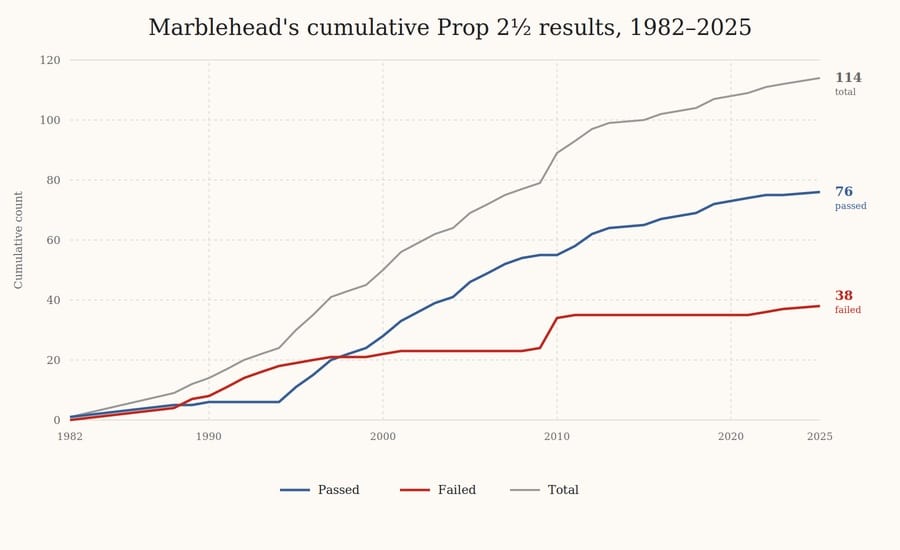

EDITOR’s NOTE: We’ve compiled 44 years of Proposition 2½ votes into an interactive graphic showing every ballot question Marblehead voters have faced since 1982. Explore the data, see how pass rates have shifted by decade and discover which projects earned the strongest support. View the full visualization by clicking here.

Marblehead voters will fund things they can see and touch, but they have not approved a general operating budget increase in more than 20 years.

That distinction is not episodic. It is structural.

A Marblehead Independent analysis of every Proposition 2½ vote presented to Marblehead residents since 1982 reveals 114 ballot questions spanning 44 years. Voters approved 76 overall, but the outcomes split sharply by question type. Debt exclusions for capital projects passed 68 times and failed 16 times. Capital exclusions for one-time expenses passed five times and failed four times. Operating overrides passed three times and failed 18 times.

Under Proposition 2½, not all tax increases function the same way. A general operating override permanently raises the town’s tax levy to fund ongoing expenses such as salaries and services. A debt exclusion temporarily raises taxes to pay off bonds for specific capital projects and expires once the debt is repaid. A capital exclusion similarly funds one-time purchases without permanently increasing the levy. An underride allows voters to reduce the tax levy below the maximum allowed.

Finance Director Aleesha Benjamin said the town’s long-range forecast projects a widening structural gap: roughly $7 million in fiscal 2027, $11 million in fiscal 2028 and $15 million in fiscal 2029.

The fiscal 2026 budget adopted at Town Meeting totals $128 million but relies on $7 million in free cash, one-time surplus funds, to balance recurring expenses. The town’s forecast shows free cash use declining even as Marblehead plans for higher debt service and absorbs major cost increases.

Health insurance represents one of the largest uncertainties. Benjamin said she initially projected increases in the mid-teens, but later information suggested that estimate may have been low. Trash collection costs are projected to rise by $800,000 to $1 million in fiscal 2027 alone. Special education adds another layer of unpredictability, with out-of-district tuition exceeding budgeted amounts in recent years.

The pattern holds across economic cycles, political leadership and voter turnout. What changes is not the result but the pressure that builds around it.

If this helped you understand how Marblehead approaches tax increases, that clarity came from hours of shoe-leather reporting — poring over decades of town reports in the Marblehead Room at Abbot Public Library, cross-checking state data, compiling election results and setting up interviews. Right now, 95 readers support The Marblehead Independent with recurring monthly or annual contributions, and we’re aiming to reach 100 by Jan. 31 so we can keep doing this work as fiscal 2027 decisions come into view. This reporting turns up records into context you can actually use before votes are cast. Click here to become an Independent member.

Debt exclusions pass 81% of the time; operating overrides fail 86% of the time

Since 1999, voters have approved three new school buildings: the high school, Glover School and the Lucretia and Joseph Brown School. The Brown School project alone cost $54.8 million, with a $13.9 million state grant, leaving $40.9 million for local taxpayers to finance through bonds. Voters have approved the purchase of fire apparatus, including a quint fire truck in 2012 and pumper trucks in 2016 and 2021. They funded Ocean Avenue Causeway seawall reconstruction, Fort Sewall repairs and restoration of the Abbot Hall tower.

What they have not done is approve a general operating budget increase since June 15, 2005, when $2.73 million was permanently added to the annual tax base. General operating budget increases failed in 2022 and 2023, even as costs have risen faster than the 2.5% annual tax levy growth allowed under Proposition 2½. Town Administrator Thatcher Kezer said health insurance costs rise 15% to 17% annually, while the cap limits revenue growth regardless of cost increases.

The early years of Proposition 2½ brought sustained voter rejection. Between 1982 and 1989, voters approved four override proposals and rejected eight. The early 1990s showed continued resistance, with six consecutive operating override failures between May 1991 and June 1992, including a $508,000 request for Meals on Wheels that failed 716–782.

By the mid-1990s, capital projects began passing. On June 10, 1996, voters rejected an $870,084 school operating override by a 2,737–3,373 margin but approved debt exclusions for surface drains, school computers worth $581,500 and fire equipment worth $462,000. On June 14, 1999, voters approved funding for construction of a new high school by a 4,659–2,974 vote.

During the 2000s, voters were more generous in approving tax increases, with 31 of 34 override questions approved. But distinctions remained sharp: operating requests continued to struggle even as capital projects advanced.

June 15, 2010: Voters reject all 10 override questions

That distinction collapsed entirely on June 15, 2010.

Voters were presented with 10 override questions and rejected all 10. A landfill closure failed 1,956–3,875. Sidewalk repairs for $100,000 failed 1,639–4,184. Piper Field turf failed 1,723–4,097. Glover School construction failed 2,020–3,940. Combined, the 10 questions received 21,065 yes votes and 37,027 no votes.

The wipeout came 18 months after the September 2008 financial crisis.

On June 14, 2011, a revised Glover School proposal returned to the ballot and passed 3,394–2,753. The final school construction project cost $25.9 million, with a $10 million Massachusetts School Building Authority grant, leaving roughly $16 million for local taxpayers to finance.

Marblehead resident Jack Buba, a former Finance Committee member, said the Glover School votes show how debt exclusions can function as a price check when voters reject a project as too expensive and officials return with a revised proposal.

“It failed. And we said, ‘Look, that’s too much,’” Buba said. “And they came back $5 million cheaper the next year — and it passed.”

Buba said the voting pattern reflects how Proposition 2½ has been used in practice.

“People are using the debt exclusions as a tool to allow them to spend more,” he said. “Essentially, it’s an end run around Prop. 2½.”

He argued the deeper issue is timing and priorities. Towns use levy growth for recurring costs, then return to voters for capital work after facilities deteriorate, often aligning major maintenance with the expiration of prior debt rather than when the work is required.

In Buba’s view, that dynamic produces grudging support for buildings while leaving voters skeptical of permanent budget growth. Asked why operating overrides keep failing, he said he views it as a rejection of management.

‘Debt overrides are transparent, specific and directly accountable’

Select Board member Moses Grader, the former Finance Committee chair, offered a different explanation for the divide between capital and operating votes.

“Debt overrides are transparent, specific and directly accountable,” Grader said. “Operating budgets are generally not as clear. Too many discretionary components. Less accountability around why increases are happening.”

Grader said the roughly $1 million increase in health insurance costs is “hugely material” and argued that voters are more likely to approve an override when the request is limited to a clearly defined expense — one that makes the case, in his words, a “no-brainer.”

He has described this as a “menu approach,” in which voters approve or reject individual cost items rather than general budget increases.

The creator of the Proposition 2½ system lived on Village Street in Marblehead.

The late Barbara Anderson, who became known as the “mother of Prop. 2½,” served on the Marblehead Finance Committee from 1978 to 1981 while leading the statewide campaign that created the law. The Nov. 4, 1980, statewide vote passed by a 400,000-vote margin. Marblehead voters embraced the measure decisively, casting 8,565 yes votes and 3,658 no votes out of 12,425 ballots cast, an 86.4% turnout.

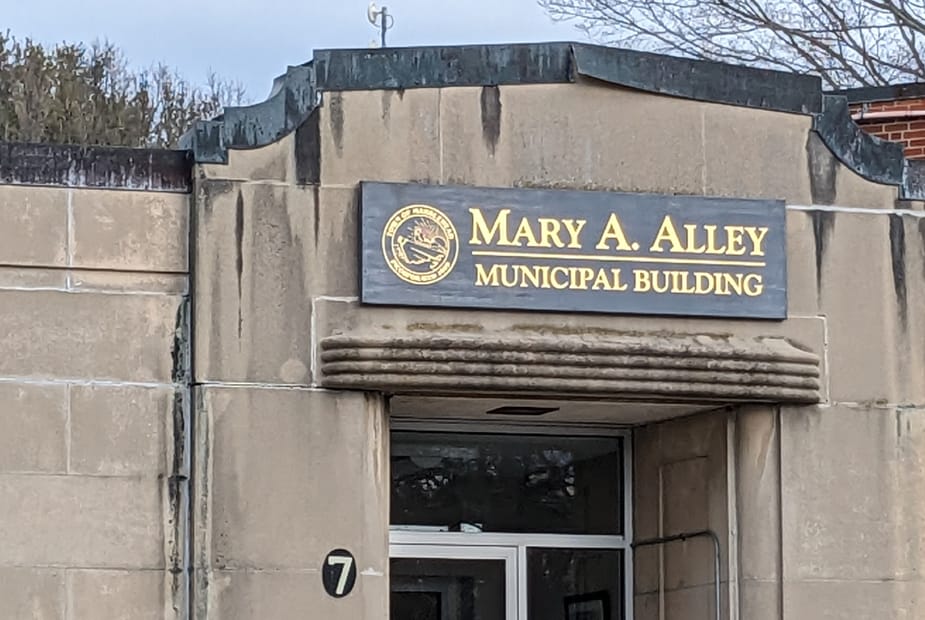

The law capped annual property tax levy growth at 2.5% plus new construction value unless voters approved an override. Since June 19, 1982, Marblehead has followed those requirements 114 times, most recently on June 10, 2025, when voters approved two debt exclusions totaling $14.35 million for a Marblehead High School roof and HVAC project and renovations to the Mary Alley municipal building.

Kezer said one option towns can use — but Marblehead has not — is building levy capacity by not taking the full 2.5% increase each year, creating room for future cost growth without immediately seeking overrides. Marblehead has not employed that strategy. The town maximizes the 2.5% increase each year.

The choices Marblehead has made over 44 years now frame decisions ahead for fiscal 2027.

Whether Marblehead voters would approve an operating budget override in 2026 or 2027 remains uncertain. The 44-year record suggests capital projects pass while permanent budget increases fail.

Across 114 votes from 1982 through 2025, Marblehead voters have built schools, renovated historic buildings, upgraded fire equipment and repaired seawalls through temporary tax increases totaling tens of millions of dollars. They approved school construction in 1999, 2008, 2011 and 2019. They rejected school operating budget increases in 1996, 2022 and 2023.

The system voters created rewards specificity, visibility and reversibility. Town officials now manage schools on operating budgets constrained by a tax cap that grows more slowly than the costs those buildings generate.

That tension — not voter inconsistency — is the central fact shaping Marblehead’s fiscal future.

Get our free local reporting delivered straight to your inbox. No noise, no spam — just clear, independent coverage of Marblehead. Sign up for our once-a-week newsletter.