Table of Contents

Get the latest from The Marblehead Independent delivered straight to your inbox.

The Marblehead Museum unveiled the results of a $1.4 million renovation of the 1768 Jeremiah Lee Brick Kitchen on Saturday, hosting a gala that marked both the building’s preservation and its future role in telling a fuller story of the town’s past.

Guests in cocktail attire mingled through the meticulously restored two-story brick building and out into a tented garden strung with lights, champagne glasses in hand. The evening featured performances by Northeastern University’s a cappella group Pitch, Please! and an elegant spread from Vinwood Catering as donors, volunteers and community members toured the building, celebrating a renovation project that began in 2021.

“We wanted a public opportunity to thank the many, many people who supported the project in many different ways, not just through donations, but through the work that they did or the volunteer time that they spent,” said Lauren McCormack, executive director of the museum.

The evening began with attendees gathering in the brick courtyard before being welcomed into the building through its newly accessible entrance. Inside, visitors moved through the first floor, which has been transformed into exhibition space that will soon house displays on Marblehead’s history, including the lives of enslaved individuals who lived and worked on the property.

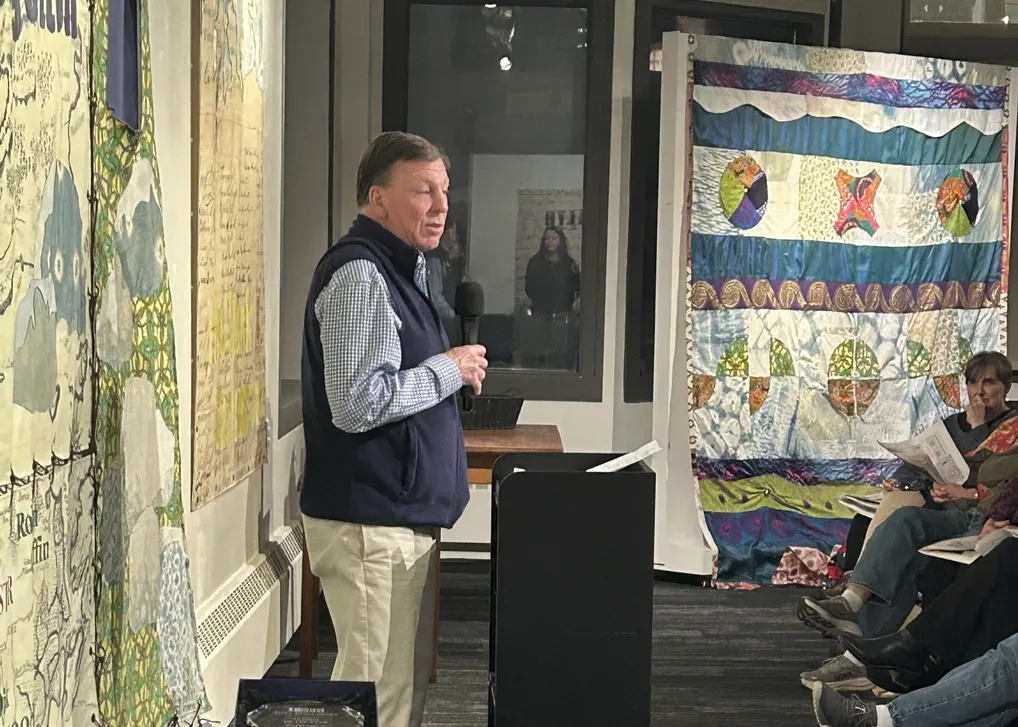

In a highlight of the evening, museum president Patty Pederson formally dedicated the first-floor exhibition space as the Ted and Julie Moore Family Fund Exhibit Gallery, recognizing the couple’s transformative $150,000 gift that helped push the project over the finish line.

“We are honored to name the first floor exhibit gallery after you both and your family,” Pederson told the Moores, who were in attendance. Their contribution came at a critical juncture when the project faced funding challenges, including a rescinded federal grant that had threatened progress.

“That was huge,” McCormack said of the Moores’ gift. “That helped us get over the finish line. And so that’s why it was important to us for that generosity, to name this exhibit hall.”

The renovated structure features a recreated 1760s fireplace built by Tom Peach and Fiachtra Daly, with every detail carefully researched and reproduced. Original wooden beams remain in place but have been reinforced with modern supports and wrapped in removable Tyvek to allow for future research. Numerous electrical outlets line the walls, strategically placed to accommodate future exhibit cases.

Visitors noted the dramatic transformation from what had been the beloved Litchman-Orne Print Shop into a state-of-the-art exhibition and research facility. Bruce Greenwald served as architect for the project, working with structural engineer Ed Moll to address numerous challenges, including damaged masonry, deflected roof timbers and powderpost beetle damage in the building’s original beams.

“The building is completed, and we started the move in process. But it won’t be till the winter that we’ll be fully moved in to the second floor Research Center and then the first floor exhibit,” McCormack explained. “The goal is early 2026 for the exhibit down here. You know, it’s been a little delayed due to funding.”

Upstairs, the second floor has been converted into “The Standley Goodwin Research Center,” named for the project’s largest benefactor whose donations totaled approximately $650,000. The space includes climate-controlled archival storage rooms, a collections processing area where volunteers inventory and describe materials, a reference library filled with Marblehead history books, a break room and offices for staff members.

“As you all saw, the second floor provided us with an opportunity to expand our archival storage, collections processing and research facilities,” Pederson told attendees. “We have now state-of-the-art collections storage with humidity and climate controls. The second floor provides the museum a safe, beautiful space to share our collection of over 40,000 photographs, documents and archival items with the Marblehead community, genealogists, academics and other researchers.”

Original elements from the 1870s Mugford Hall era have been preserved in the ceiling, including medallions and decorative stenciling dating to when the space served as a fire station and community gathering place. The museum has maintained this connection to the building’s past life as Mugford Hall, where organizations including the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Shoe Cutter’s Union and Boy’s Prayer Club once gathered.

The renovation project began with intensive research and documentation. Dendrochronology studies dated timbers to the 1760s, while careful examination of brick patterns revealed evidence of how the building had been modified over time. Archaeological excavations by UMass Boston’s Department of Archaeology uncovered elements of the original cobbled courtyard.

“We didn’t understand how the building had changed over time until the research phase,” McCormack said. “When we started to peel the layers back, we realized the building had been added to, the building had been lifted. It was originally a one-story building, and then it became a two-story. And then it became a much bigger two-story building.”

Archaeological research confirmed that the front half of the building originally served as a carriage house, while the back half contained the kitchen and slave quarters. Records show the Lee family owned three enslaved individuals when the mansion was built in 1768 — Gemma, Cupid and Diamond — along with a fourth person whose name has been lost to history.

“I think it really focused us in on the role enslaved people had in Marblehead, and not just on the Lee estate, but what they contributed to the town through their forced labor,” McCormack reflected.

According to the 1765 census, approximately 100 people of color lived in Marblehead at that time, with many being enslaved. The museum’s inaugural exhibit in the Moore Family Fund Gallery, “Resistance and Resilience: Slavery and Freedom in Colonial Marblehead,” scheduled to open in early 2026, will explore how enslaved individuals built lives despite their circumstances in colonial Massachusetts.

Elizabeth Freeto, a museum volunteer, explained how the project has deepened her understanding of Marblehead’s social dynamics. “I think it has brought me a much better understanding of day to day social interactions and functions of the different levels of society,” she said.

In addition to the Moores and Goodwin, the museum recognized numerous other contributors to the project, including the Garden Club, the Orne family who sold the building to the museum and past president Maura Phelan and former treasurer Pat Lausier, who helped guide the purchase and early renovation planning.