Table of Contents

Get our free local reporting delivered straight to your inbox. No noise, no spam — just clear, independent coverage of Marblehead. Sign up for our once-a-week newsletter.

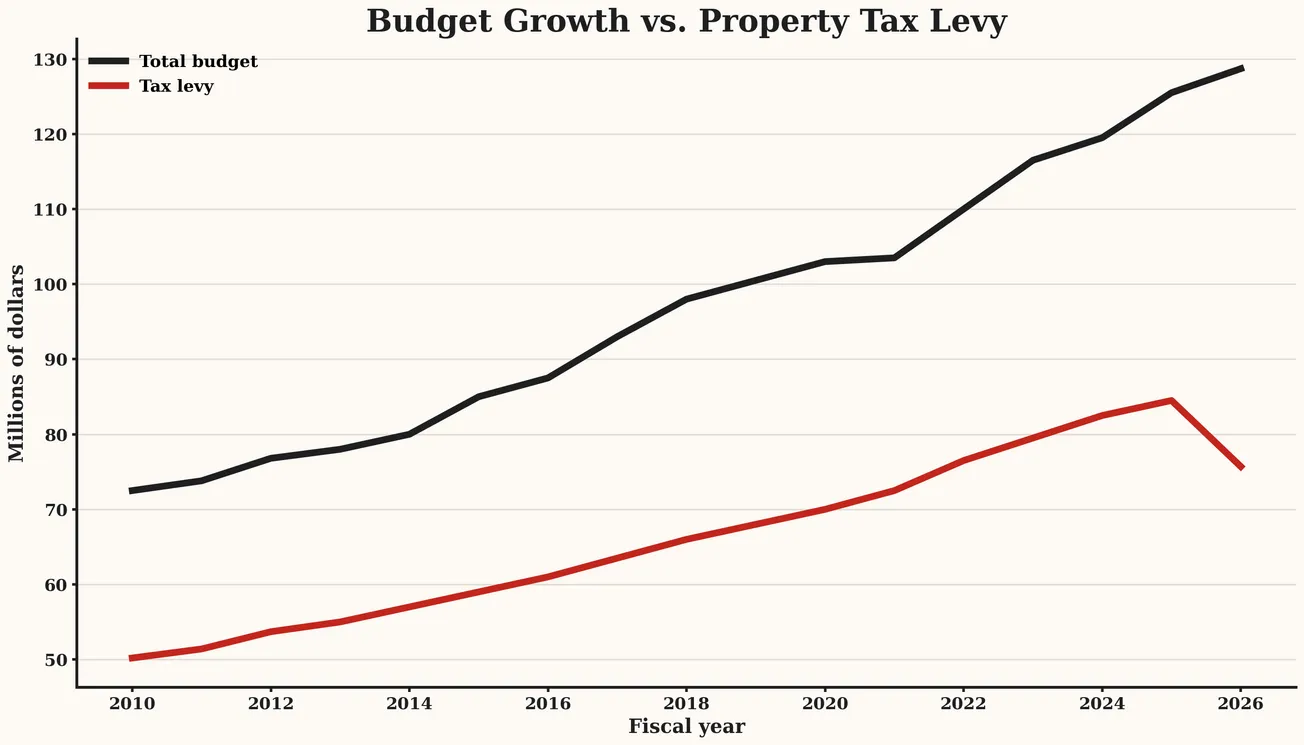

Marblehead’s budget keeps getting larger, yet the amount of flexibility inside it continues to narrow.

For fiscal year 2026, Town Meeting adopted a $128 million operating budget, the annual plan that pays for schools, public safety, public works, employee compensation, retiree benefits, utilities, contracts and debt service. The total is higher than in prior years. Still, the conversation around town finances has shifted away from expansion and toward constraint — how long rising costs can be absorbed within revenue limits set by state law.

That tension does not hinge on a single vote or a single year. It is built into how Marblehead raises money and how its largest expenses behave over time, a reality that produces different conclusions depending on where residents place their priorities.

Right now, Finance Director Aleesha Benjamin notes the town’s long-range financial forecast projects a widening structural gap in the years ahead — roughly $7 million in FY2027, $11 million in FY2028 and $15 million in FY2029,

You’re able to read this reporting free because 81 Marblehead neighbors support it through monthly and annual contributions. Putting this piece together meant tracking years of budget data, building original charts, reading financial documents and staying with the story long enough to explain what’s changing — and what isn’t. We’re working toward 100 members by Jan. 31 so we can keep doing this kind of careful, time-intensive reporting on town finances. If you’ve been meaning to support this work, becoming an Independent member helps make it possible. Click here to become an Independent member.

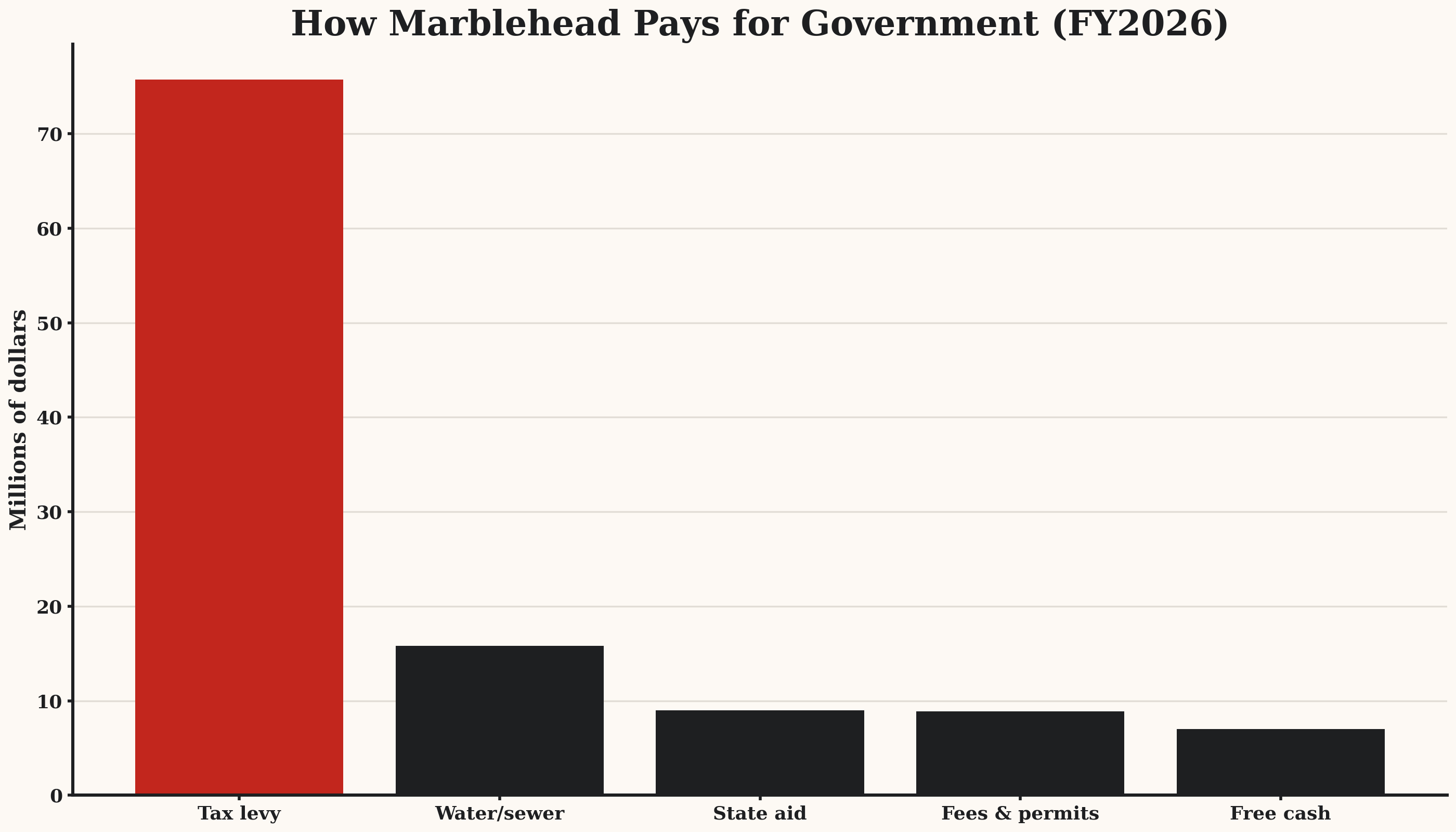

How Marblehead pays for government

Property taxes remain Marblehead’s primary revenue source. In FY2026, they account for about $75.7 million, roughly 59% of the total $128 million budget.

Under Proposition 2½, the town’s property tax levy may increase by no more than 2.5% per year, plus additional revenue from new construction and certain improvements, known as new growth. The structure provides predictability but limits how quickly revenue can rise, regardless of cost increases elsewhere in the budget.

State aid contributes about $9 million, or roughly 7% of the total, while local receipts — including permits, fees and investment earnings — add another $8.9 million, also about 7%. Those sources fluctuate with economic conditions and state policy.

To balance the FY2026 budget, Marblehead used $7 million in free cash, certified surplus from prior years, equal to about 5% of the total budget. The plan also includes $9.1 million in debt exclusions, temporary property tax increases approved by voters to pay for specific capital projects.

Together, those revenues add up to a balanced budget. What they do not guarantee is flexibility when major costs rise faster than the levy allows.

Costs that move faster than revenues

On the spending side, Marblehead’s largest expenses tend to grow steadily or unpredictably, often outpacing the town’s most reliable revenues.

Personnel costs dominate the budget. According to the town’s long-range financial forecast, staff costs account for roughly 80% of spending. Salaries, step increases and cost-of-living adjustments are governed by multi-year contracts that provide stability for employees and services, but also lock in future increases once agreements are signed.

Health insurance is one of the most volatile line items. Costs depend not only on overall rate increases, but also on how employees enroll across multiple plans, each with different price points.

“The challenge of nailing down the health insurance numbers is they’ll give us general increases,” Town Administrator Thatcher Kezer told the Independent. “But the real number that needs to be calculated is we have all our employees who decide, out of the eight plans, or whatever the number is, of plans they’re going to participate in that have different cost amounts.”

Enrollment shifts can significantly affect the bottom line, he said.

“So if you just apply a 14% general number,” Kezer said, “this health plan which has 50 employees, and it may be going up 25%, and this health plan that has eight employees is only going up 6%, we’re getting hammered more than the 14%.”

Benjamin said the uncertainty extends beyond Marblehead.

“I’ve gone to several conferences, seminars with some of the insurance companies, who are saying, in the private, commercial market, they’re seeing anywhere from 23 to a 26% increase,” Benjamin said. “But they said for us, for municipalities, especially in the General Insurance Commission, that we can expect two-digit increases for the next two to three years. It’s not going to go too far down.”

Benjamin said she had initially projected increases in the mid-teens, but later information suggested that estimate may have been low.

“When the actuary came in, he said I was kind of low for what he had heard,” she said.

Solid waste and other service contracts represent another pressure point. The town’s forecast anticipates a $800,000 to $1 million increase in trash collection costs in FY2027 alone, a change equal to nearly 1% of the entire FY2026 budget in a single category. Like health insurance, those costs are shaped by regional markets rather than local policy choices.

Retirement obligations add a longer-term dimension. Marblehead’s most recent retiree health report shows a net OPEB liability of about $142 million, exceeding the entire FY2026 operating budget. While the full liability stretches decades into the future, annual costs appear each year in the operating budget, limiting how much of the $128 million total is truly discretionary.

Special education: mandated services, uneven costs

Special education costs add another layer of unpredictability to the budget.

Enrollment in Marblehead Public Schools has declined by an average of about 3.9% per year, falling from 2,754 students to 2,511, a pattern administrators said is spread across grade levels and does not easily translate into staffing reductions.

At the same time, special education spending has repeatedly exceeded projections. The FY2026 school budget includes $3.56 million for out-of-district special education tuition, but officials said actual costs reached about $3.3 million in FY2025 and $4.4 million in FY2023, driven largely by a small number of high-needs placements.

Those costs are not discretionary. Federal and state law requires districts to provide appropriate services regardless of expense, leaving little short-term flexibility when student needs change. While the state’s special education circuit breaker reimburses a portion of qualifying costs, payments lag by a year and do not cover the full amount, requiring the town to absorb increases upfront.

As Marblehead plans for FY2027, officials say that volatility remains one of the most difficult pressures to forecast, even if overall staffing and programs remain steady.

Why staffing changes are complicated

Residents who oppose tax increases often ask whether staffing levels can be reduced instead. Officials say the answer is not straightforward.

“When people say, ‘We’re down X number of students, so we don’t need as many teachers,’ that would be true if all the students belonged to one particular class,” Kezer said. “They’re spread out over 12 grades.”

Small enrollment declines across multiple grades do not necessarily translate into the ability to eliminate positions without affecting class sizes or programs, he said.

“It’s not as simple and straightforward as people think,” Kezer said.

The same dynamic applies on the municipal side, where retirements do not always produce savings.

“You would think that you’ve got people moving up the steps, so you’re increasing the cost, but you have people retiring — they’re at the top step — and they’re being replaced with people at a much lower step, that there’s savings,” Kezer said. “However, in the employment marketplace, we’re having to bring people in at the higher steps to get them to take the job.”

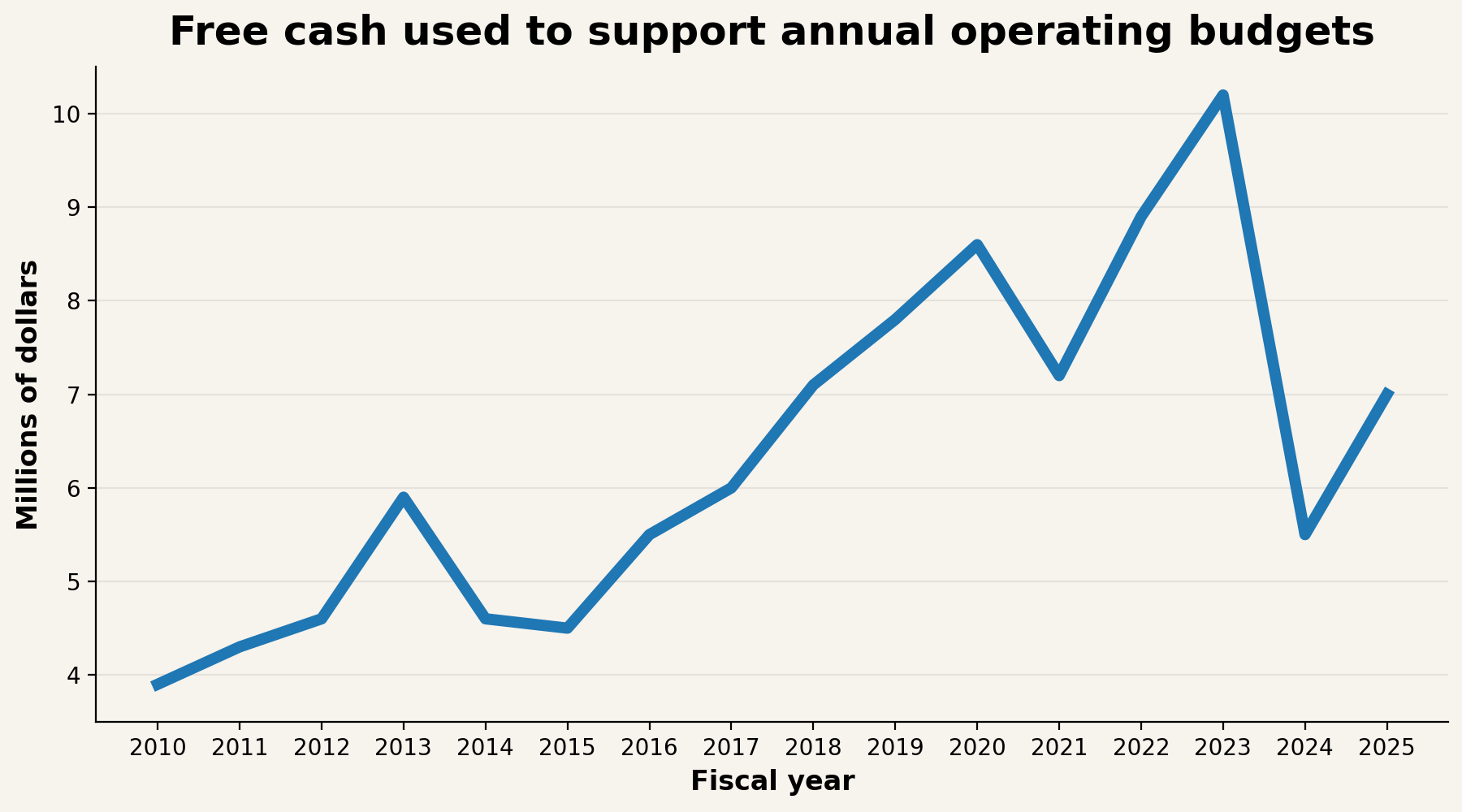

Free cash: one-time relief, shrinking margin

The FY2026 budget relies on $7 million in free cash — one-time surplus funds — to balance recurring expenses.

Part of the decline in available free cash reflects improved budgetary discipline, as the town has become more accurate in projecting actual costs, leaving less unspent money at year-end to certify as surplus.

That approach becomes harder in FY2027. The town’s financial forecast shows free cash use declining to about $5 million, even as Marblehead plans for higher debt service and absorbs major cost increases, including the projected rise in the trash contract and continued pressure from health insurance, personnel and special education.

Free cash can help bridge gaps in a single year, but it does not recur. Once drawn down, it cannot support ongoing costs tied to multi-year obligations or permanent staffing.

As reliance on free cash is reduced, fewer one-time dollars remain available to cushion the budget, increasing dependence on recurring revenue sources constrained by Proposition 2½.

Oversight and uncertainty

Finance Committee Chair Alec Goolsby has framed the budget discussion as an exercise in realism rather than prediction.

“I don’t think this exercise, a takeaway is we should be looking at these numbers and thinking we have an override request even on the table yet,” Goolsby said. “Until we do the next step to really figure out, how can we address it before asking for an override.”

Goolsby said the committee’s focus has been on understanding where assumptions may change and where caution is warranted.

“As a finance guy, I’m very concerned about overstating stuff,” he said, referring to health insurance projections. “I’m arguably understating the impact from what she’s hearing.”

That approach reflects a broader effort to avoid what officials describe as foregone conclusions.

“The numbers are what they are,” Goolsby said elsewhere in the discussion. “You do your best to come up with a budget that meets a two and a half percent override.”

Opposition to tax increases

Not all residents agree on how Marblehead should respond to rising costs.

Many who oppose tax increases have cited affordability concerns, particularly for residents on fixed incomes. Others argue that cumulative increases matter more than any single year’s change, even when individual increases appear modest. Some question whether all spending growth is unavoidable, urging the town to look harder at service levels, staffing and regional collaboration before seeking additional revenue.

Those perspectives are familiar to town officials.

“Who wants to raise their money?” Kezer said. “In communities, different personalities — you’re in a tough way.”

At the same time, he said, the budget ultimately reflects the cost of providing services residents expect.

“You’ve got to have a tax levy, the taxes you’re collecting, sufficient to cover all of the services that you’re providing,” Kezer said. “You can’t fake that.”

Using hypothetical numbers, he said underfunding does not resolve the underlying math.

“You can’t fund 15 officers and think you’re going to have 33,” he said. “The numbers just catch up to you.”

A narrowing margin

The effect of rising fixed and semi-fixed costs is a shrinking margin for discretionary choices within the $128 million budget. As more dollars are committed to salaries, benefits, contracts and debt service, fewer remain for maintenance, equipment replacement or new initiatives.

Benjamin said the town remains required to produce a balanced budget, regardless of the choices involved.

“There is going to be an impact, right?” she said. “It’s not fair. It’s just it is, but it is balanced.”

Goolsby said that narrowing margin is the core challenge.

“I’ve been working on the Finance Committee for a very long time,” he said. “I’m always wondering what I’m missing, but I feel like I’m not missing that much anymore.”

Marblehead can produce a balanced budget each year, but more of the $128 million is spoken for before debate begins. Whether residents believe the answer for FY2027 is service reductions, new efficiencies or additional revenue remains an open question.