Table of Contents

Get the latest from The Marblehead Independent delivered straight to your inbox.

Dozens of newly unearthed photographs documenting daily life at the Children’s Island Sanitarium off Marblehead’s coast have been donated to the Marblehead Historical Commission, offering a rare visual window into a chapter of local history that spanned six decades.

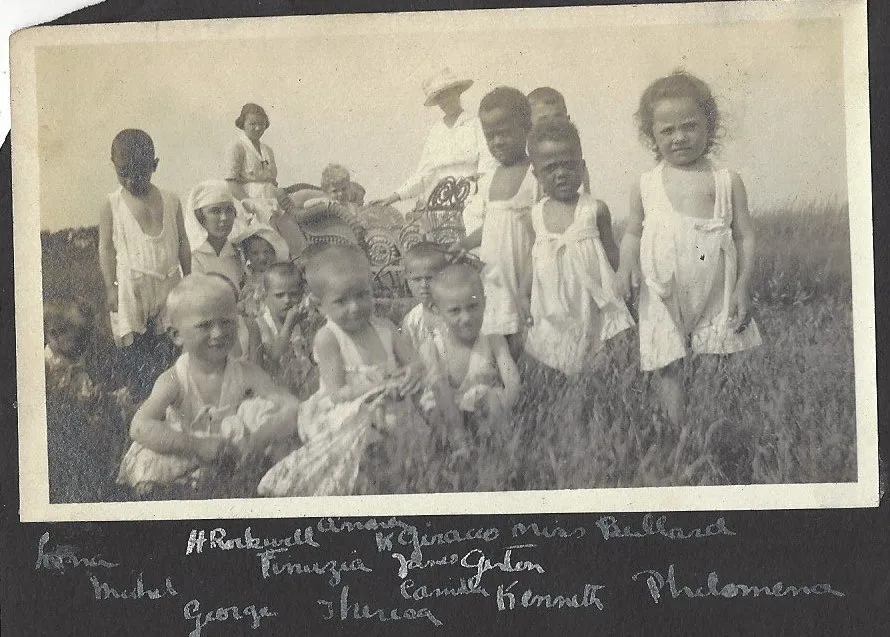

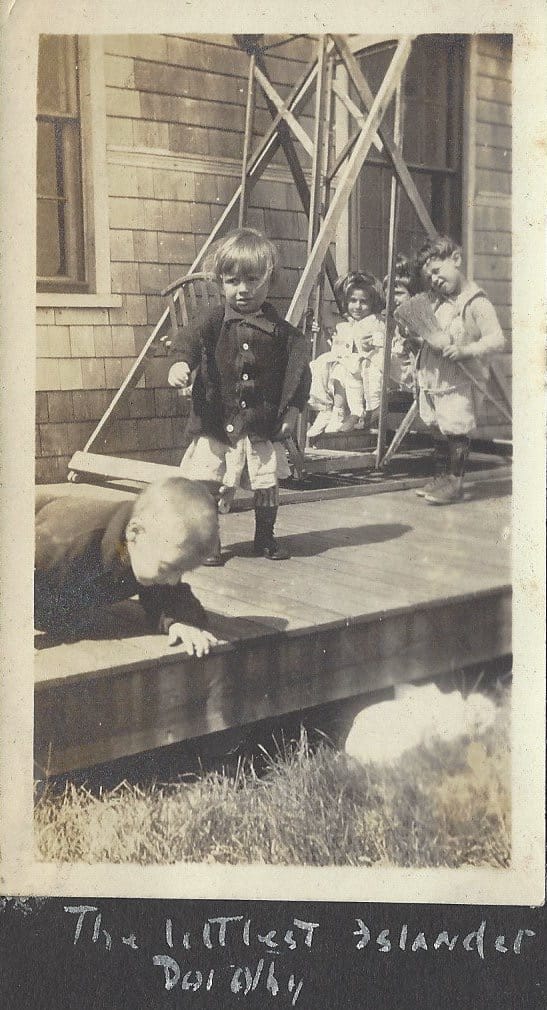

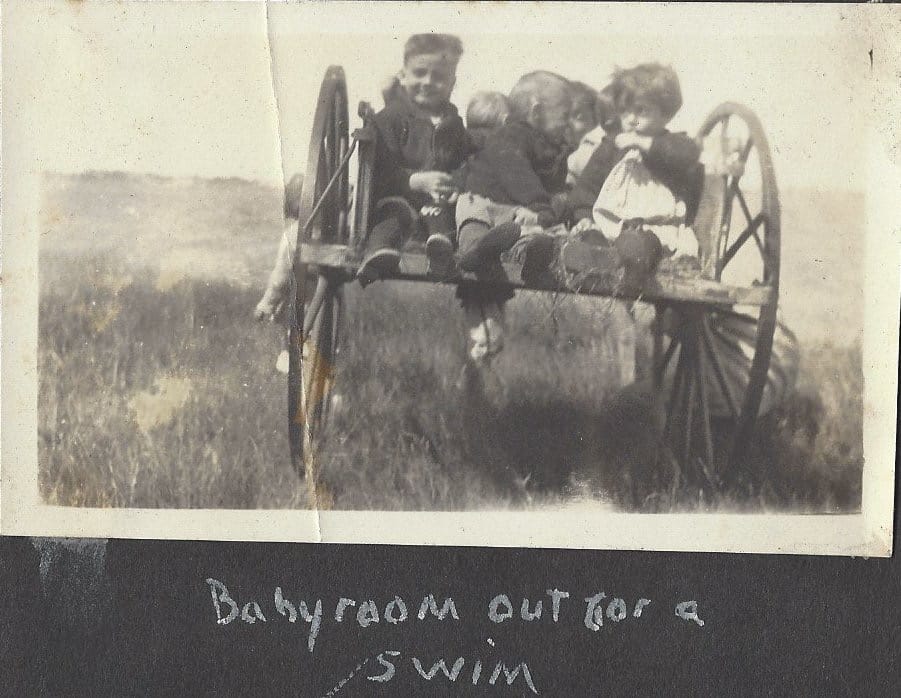

The collection, dating largely to 1917-1918 and the 1920s, captures children and staff at the Children’s Island Sanitarium — then known as Cat Island — which provided summer care for children with chronic but noncontagious conditions. Preserved in family albums and labeled with handwritten captions, the photographs are digitized and cataloged for public access.

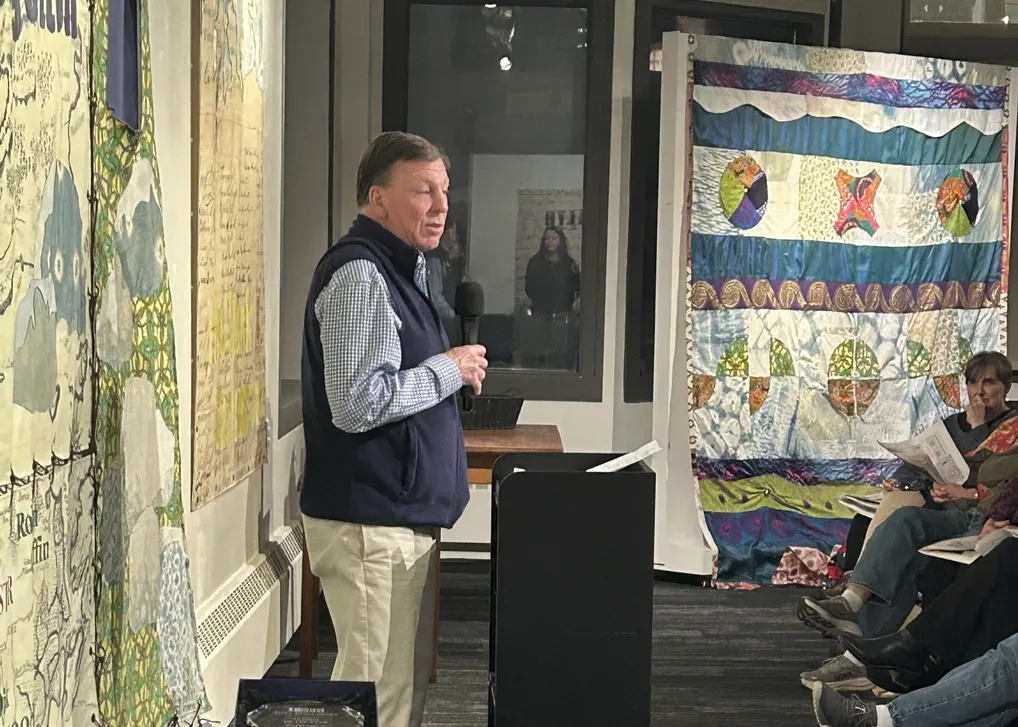

Marblehead Historical Commission member Peter Stacey, who examined and cataloged the donation for the commission, said the material’s significance was immediately clear.

Stacey said, “When I opened them up and got into it, I said, ‘We have to get these online, because this is - this is a whole story here.”

Salt air as medicine

The Children’s Island Sanitarium operated from 1886 to 1946, serving as a seasonal refuge where children between the ages of 2 and 12 could regain strength in the sea air.

The decision to locate it on the island was deliberate. Donor Frederick Rindge, whose family had purchased the property, stipulated that children of “every race, color and religion” be welcomed. The Lowell Island House, a failed seaside hotel, was repurposed into dormitories, dining halls and airy porches, its broad piazzas and rocky coves becoming both hospital and playground.

For the first 15 years, the institution was run by the Anglican Sisters of St. Margaret of Boston, who had experience with sick children — many with disabilities, too, at hospitals in Boston and Winthrop. They supervised every aspect of life, from medical care to playtime. When the sisters withdrew around 1900, a new board of managers took over, led by pediatrician Charles E. Inches and later Philip L. Saltonstall. Superintendent Lucy W. Davis, a trained nurse, oversaw operations.

Increasingly, the work was carried out by young women volunteers, many serving three-week rotations. They dressed and bathed the children, managed braces and splints and served meals — duties considered too important to entrust to untrained attendants.

The children themselves came largely from Boston’s poorest neighborhoods, referred by social workers or physicians. Though contagious illnesses such as tuberculosis were barred, the sanitarium welcomed children with rickets, spinal conditions, rheumatism, asthma and heart ailments. For many, the fortnight or summer they spent on the island was their only chance at fresh air, regular meals and structured care. Contemporary accounts describe wards filled with children recovering from polio, asthma and osteomyelitis, their wounds tended by visiting doctors and volunteer nurses who lived in spartan quarters without fresh water.

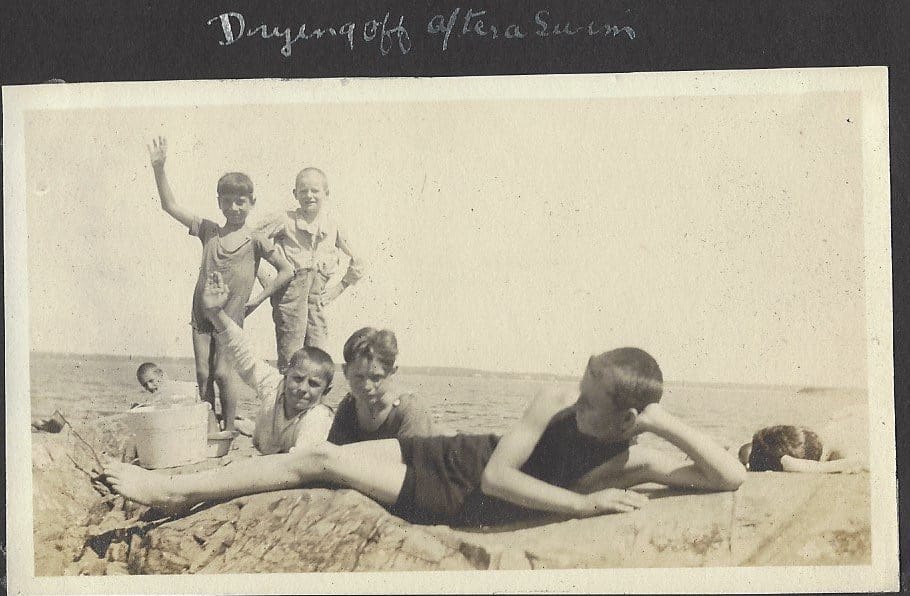

The photographs capture scenes that challenge common perceptions of early 20th-century medical facilities. Some show rows of beds rolled out onto porches for heliotherapy, while nurses in starched uniforms kept careful watch. Others depict groups scrambling over the rocky shoreline, their faces bright with smiles in images labeled “Boys on the rocks” and “Girls on the rocks.”

Daily life extended well beyond treatment. One image labeled “Dinner on the ward” shows children gathered at long outdoor tables, while another, titled “The great day the funny man came,” records a performer’s visit that underscored how laughter was treated as medicine. Perhaps most striking are the portraits that carry names: Clifford King, Edie McKenna, Christy. Each one gives identity to a child who might otherwise have been lost to time.

“What strikes me is just looking at the kids,” Stacey said. “They seem to be having fun. You don’t expect that. These kids look really happy.”

The charity of a town

Volunteers’ accounts reinforce the mix of hardship and joy. Maude S. Curtiss, writing in 1905 for the American Journal of Nursing, described “seventy-five pairs of heels and seventy-five shrill and lusty throats” on stormy days when children were confined indoors, but also the delight of jellyfish hunts at beaches nicknamed Shell, Crab and Bathing.

Later recollections mention laughter from dormitories, saltwater showers and the exhausting din of constant voices, but also the small triumphs of children walking again or learning to play after months of immobility.

The institution’s survival depended on broad community support, and Marblehead embraced it as its own. Fundraisers were constant, and they were reported not just locally but across Massachusetts. The Boston Globe and the Marblehead Messenger regularly carried notices of fairs, teas and benefit sales.

In 1903, residents staged a “Colonial Tea Party” at Swampscott’s historic Blaney House. Families on Marblehead Neck organized summer auctions, including a 1917 fair at Peach’s Point that raised more than $400 despite being interrupted by a sudden storm. Globe appeals often ran with a pointed message: “You can buy happiness for a child for one dollar.”

Much of the daily routine was sustained by volunteers, including Elizabeth and Martha Taintor — whose family is connected to the recent donation — who spent summers working directly with the children. Local women came in shifts, helping with meals, recreation and bedtime, often living on the island for weeks at a time.

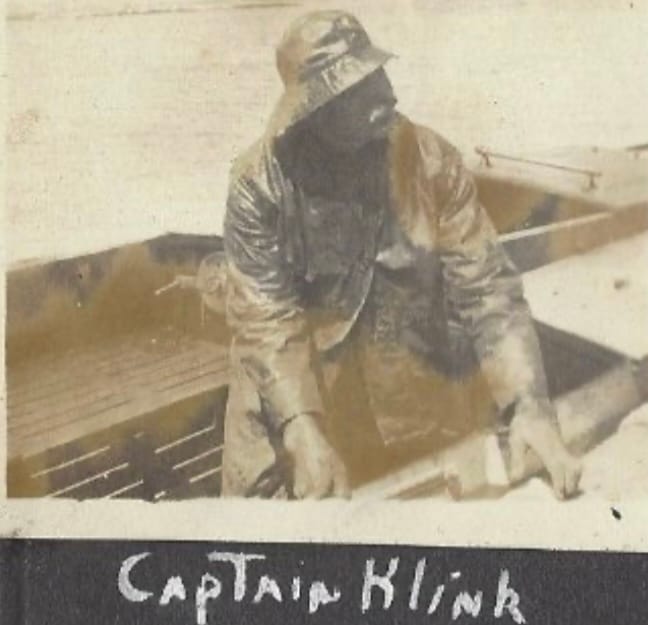

Capt. Klink and his cargo of children

Transportation, too, required local effort, and no figure loomed larger than Captain William Klink, a German-born mariner who ferried children, nurses and supplies across Marblehead Harbor. His converted power launch, the Pelican, made trip after trip each summer, carrying groups of frail but excited youngsters from Tucker’s Wharf to the island.

The Globe described the vessel as “always ready,” but Klink’s role went far beyond logistics. He became the children’s first point of adventure, their gateway to a summer of sea breezes and recovery.

Reporters recalled how girls in scarlet flannel jackets and boys in gray sweaters chattered happily as they waited in the Pelican for Klink to arrive. Those too weak to climb aboard he lifted “as carefully as a mother might,” carrying them in his strong arms up the incline to waiting wagons. A newly donated photograph shows him in oilskins at the oars of a dory, his name written boldly beneath: “Capt. Klink.”

The sanitarium was well known in its time. In 1909, the Globe reported that more than 250 children had been cared for during a single four-month season, praising the “supreme courage of the youngsters in their terrible troubles.” In 1929, Gov. Frank Allen and his wife toured the wards, greeted by children who shouted “Hey, governor” from across the room, a moment that symbolized the esteem the sanitarium held in the wider commonwealth.

Despite its prominence, the institution closed in 1946, when antibiotics rendered sea-air cures obsolete and the Boston Community Fund withdrew financial support. The island later became a YMCA day camp.

The newly donated photographs help a historical gap. Among them is “The medium sized boys at the pump,” showing a group gathered around the island’s water supply, and “Fred carrying Agnes, Ida on rock,” recording a boy lifting another child in his arms. “Young children on island” captures toddlers in sunhats, while portraits of Bobby Salto, Clifford King and others add faces to what had previously been statistics.

Each image carries both documentary value and emotional immediacy, reminding modern viewers that these were real children with names, expressions and friendships. The Historical Commission is digitizing the photographs for public access. Visitors will be able to search “Children’s Island” on its website to view the collection.

“This is history,” Stacey said. “It’s a history that I don’t think a lot of people know about. When you hit on something like this, it just gets you excited.”

Though the sanitarium closed nearly 80 years ago, the photographs highlight an enduring truth: Marblehead and its neighbors saw the island not just as a hospital but as a symbol of collective care.