Table of Contents

Get our free local reporting delivered straight to your inbox. No noise, no spam — just clear, independent coverage of Marblehead. Sign up for our once-a-week newsletter.

The buoy was just a little off.

Eleven feet of water in the channel. Chart plotter glowing. A fairly experienced captain at the helm. And then, somewhere on Lake Champlain on a July afternoon, Brew-HaHa found the rock.

Peter Evans let that moment sit a beat before the crowd at the Marblehead Yacht Club on Wednesday night. Then he said it plainly: “This dimwit of a fairly experienced captain — we hit a rock.”

Laughter. And underneath it, recognition. Because anyone who has spent real time on the water understands the particular humiliation of a chart that is technically correct and still gets you.

Evans dove on the hull at the next marina. The keel, full fiberglass, had cracked open. Fiberglass repairman Andrew Flaherty rebuilt it. Brew-HaHa kept going.

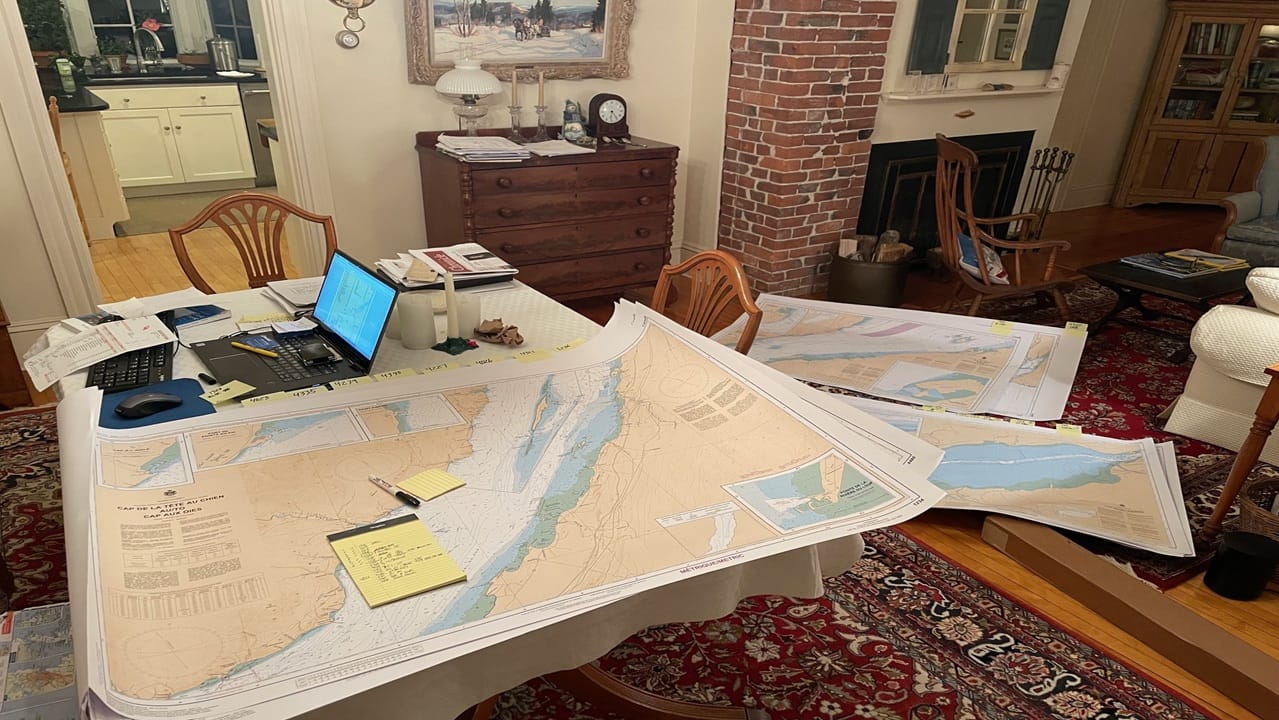

It had all started in February, in the dining room.

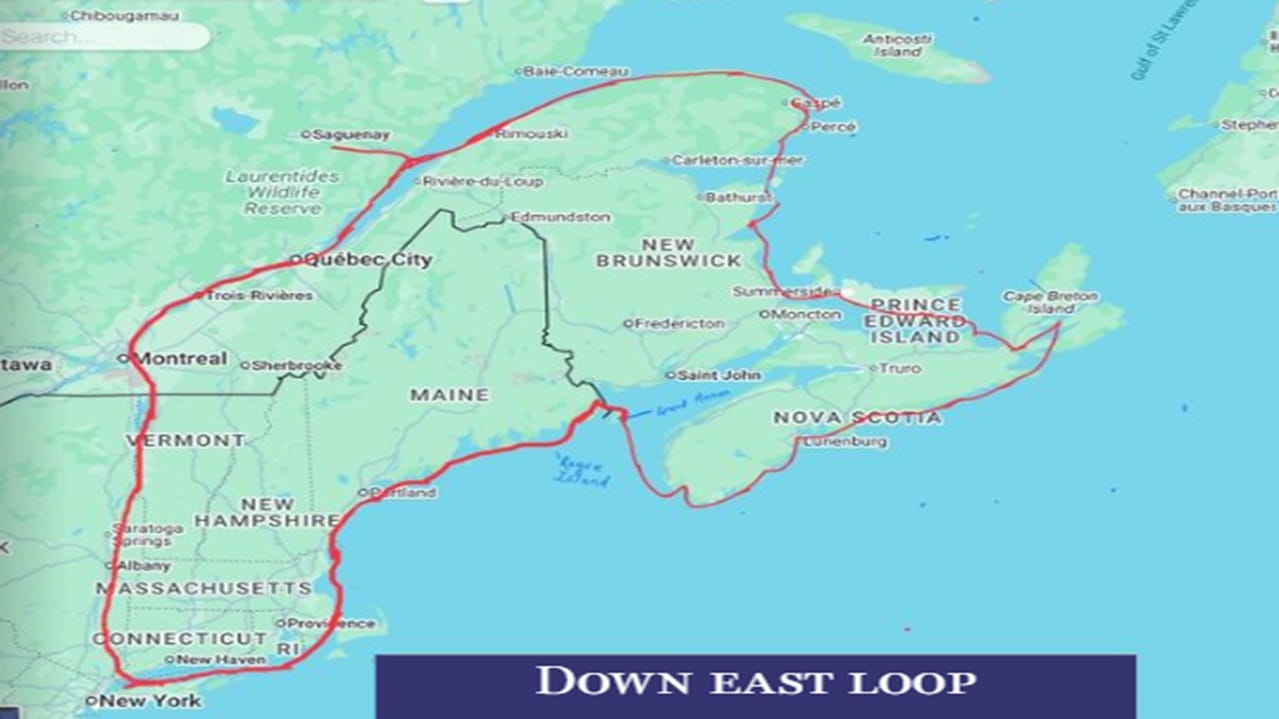

Evans and his wife, Pam Evans, had already completed a smaller loop three years earlier — roughly 1,750 miles up the Hudson, through the Erie Canal, down Lake Champlain and home. They called it “the junior varsity.” So when they began planning this one, a 2,634-mile clockwise push through New York City, upstate New York, Quebec, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, the Bay of Fundy and back down the Maine coast, Evans called it the varsity.

The preparation was systematic. Evans built a color-coded planning binder cross-referencing paper charts, navigation books and electronic routes. He ran two digital course backups daily on Navionics and Garmin. He maintained an 11-page log tracking distance, fuel purchases and the names of every person they met at each stop. Pam worked entirely from paper.

“There were times that she questioned me,” Evans told the crowd. “As you will see.”

Systems and structure

The first third of the voyage rewarded systems thinking.

Through Hell Gate and down the East River past the FDR Drive, where commuters stared from their cars. Up the Hudson past West Point and Cold Spring — where they paid $10 per hour to dock via a parking app, the only place on the trip they encountered waterfront parking meters. Through 24 locks in the Champlain Canal, where rough concrete walls ground against the hull and turbulence churned the water inside each chamber as they rose or fell. Engineered, scheduled, predictable.

Brew-HaHa, a 1988 Duffy 31, handled it with the quiet competence of a working boat doing familiar work. The Downeast hull, low and purposeful, threw a modest wake and asked nothing dramatic of its crew.

Then they crossed into Quebec, and the terrain changed.

The St. Lawrence River has a six-knot current in places and tides that demand precision. Evans described using a Canadian tide guide so accurate that they would throttle up or down to arrive at each harbor within minutes of the book’s prediction. They crossed into the Gulf of St. Lawrence — vast, indifferent, cold — where water temperatures dropped to 44 degrees and fog reduced visibility to radar returns and the green triangles of the automatic identification system (AIS) on Evans’ chart plotter.

Open water lessons

Outside the mouth of the Saguenay River, they found what Evans called the trip’s most violent moment. A combination of northeast winds and ebbing current generated steep, breaking waves that hit Brew-HaHa head-on. Sailboats that left with them arrived nearly an hour later. Evans showed the crowd a video taken just before the worst of it. Then he described the aftermath: they motored into the harbor at Tadoussac, Quebec, and the wind died and the waves disappeared within minutes, as though nothing had happened.

“It was like a little Bermuda Triangle,” he said.

There were two more crises in the open water sections. In Sorel, Quebec, 20- to 30-mph beam winds made backing Brew-HaHa into an assigned slip nearly impossible without a bow or stern thruster. Evans pulled out and re-entered repeatedly while the marina’s entire population mobilized — dock neighbors tying up extra bumpers, strangers calling directions, the captain of a 65 foot private yacht called the Dolphin guiding the final approach. In Cape-à-l’Aigle, Quebec, they departed a slip so cleanly that they forgot to unplug the 30-amp shore power cord. It tore free with what Evans described as the loudest noise he’d ever heard aboard a boat, witnessed by roughly a dozen Canadians.

“You always unplug the toaster now,” Pam said from the audience.

Hurricane Aaron shaped the final Canadian leg. Tracking the storm with the Windy app — Evans showed the crowd screenshots of orange and red forecast maps blooming over Nova Scotia — he and the crews of two other boats they had fallen in with agreed to shelter in Halifax and wait. They spent four days at the Dartmouth Yacht Club while 40-mph winds and 11-ft swells moved through. Evans called them no-go days. Tuesday night, there were guitars.

The Bay of Fundy crossing to Grand Manan Island came after the storm cleared, when forecast colors turned green. The bay holds the highest tidal range in the world, Evans told the crowd — up to 16 meters, or 53 ft, of vertical movement twice daily. They chose their window carefully and made it across. At the island’s North Head harbor, which takes no reservations and has no marina, they arrived in deteriorating weather and simply found a spot, rafting up to a sailboat that was itself rafted to another sailboat moored to a fishing vessel. Nobody gave them any trouble.

At Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, the two boats they had cruised with turned south toward home. They had been out longer. They were ready.

The Evans turned east.

The decision to keep going

That decision — small on a chart, significant in everything it implies — captures something the numbers alone don’t. They had already proved they could do the loop. The question the varsity was asking was different.

The numbers themselves are staggering enough. Sixty-six days. Forty-six marinas. Twenty-four locks. Twenty-nine fuel stops — 1,594 gallons of diesel at an average of $4.43 per gallon — with Evans manually listening to each of the boat’s two 200-gallon tanks to know when to stop pumping, repeating the process 58 times. A total trip cost of $16,112. Average fuel efficiency of 1.65 miles per gallon. A longest single-day run of 116 miles.

But the number Evans lingered on, briefly and without commentary, was the one at Roque Island on the Maine coast, near the end.

Sun going down. Steaks on the grill. A gin and tonic. He had been swimming.

“I’m good,” he told the crowd.

Before the presentation ended, Evans circled back to Lake Champlain without quite meaning to. He was answering a question about navigation when he noted, almost offhandedly, that someone had been disagreeing with his course in that channel.

“She was right,” he said.

The color-coded binder. The two electronic systems. The 11-page log. The paper charts. The current tables. The fuel spreadsheet.

They planned for everything. The rock was still there.

They repaired the keel. They kept going. That, in the end, was the varsity.

BEFORE YOU GO … Our reporting remains free and open to all. It is sustained by readers who choose to support it — by contributing so that routine, document-based local reporting continues without paywalls or promotional framing. Right now, 101 readers support The Marblehead Independent with monthly or annual contributions. Click here to become an Independent member.