Table of Contents

Arthur Miller wrote “The Crucible” in 1953, at the height of the McCarthy hearings, when Americans were summoned before congressional committees and asked to name names. He turned to Salem in 1692, where neighbors accused neighbors of consorting with the Devil and courts admitted “spectral evidence” — dreams and visions — as proof of guilt. For Miller, the witch trials were not distant history but a parable about what happens when fear outweighs reason and ideology overtakes justice. “Panic sleeps in one unlighted corner of my soul,” he later confessed. That line could serve as an epigraph for his play, which remains one of the most produced in American theater more than 70 years after its debut.

The panic in Salem was real and devastating. More than 200 people were accused of witchcraft, about 30 were convicted, and 20 were executed — 19 by hanging and one, Giles Corey, pressed to death with stones for refusing to plead. Several more died in jail. Even animals were not spared: at least two dogs were killed after being accused of serving as witches’ familiars.

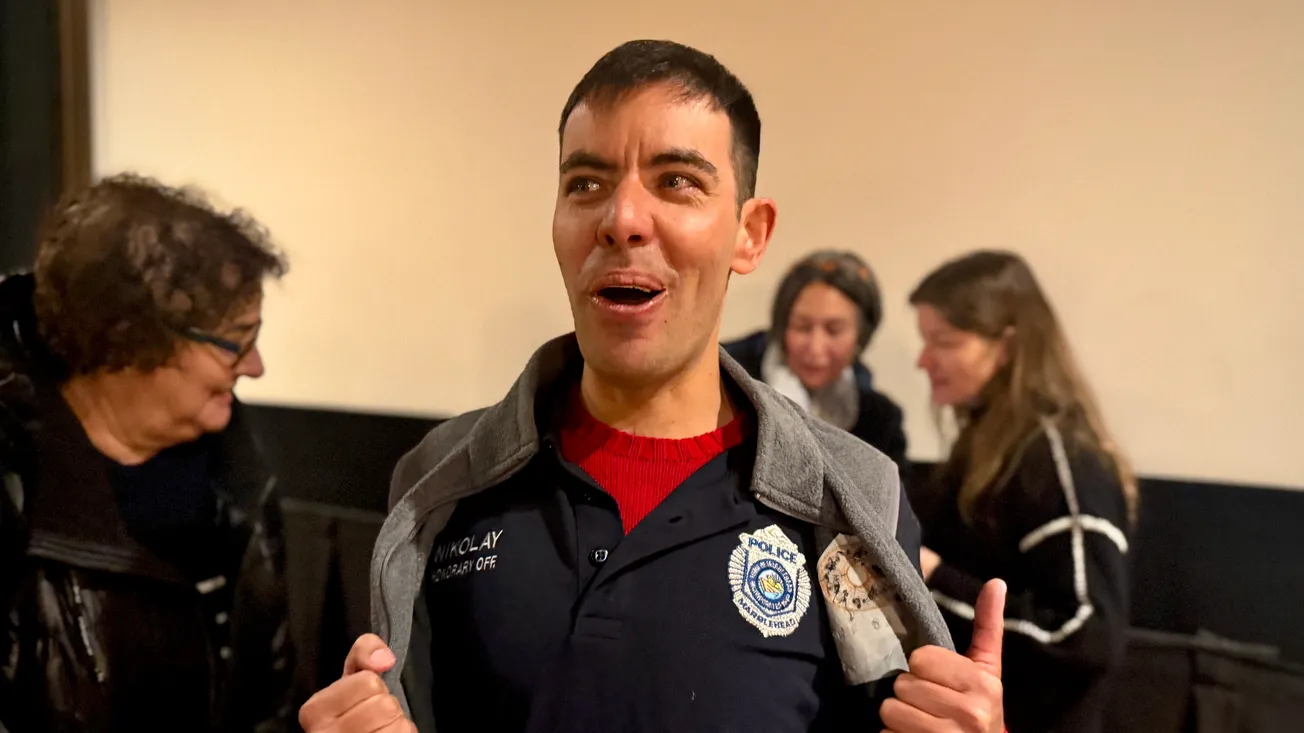

Corey’s story captures the absurdity and tragedy of Salem. Giles thought it strange that his wife was reading books he could not understand — a curiosity that, once voiced aloud, became suspicion of witchcraft. Like several passages in this play, Miller drew directly from that moment in the record, transforming it into both comedy and terror. Corey’s bafflement turns deadly when his simple question becomes evidence in court. In Marblehead Little Theatre’s production, David Foye gives Corey humor and decency, capturing genuine confusion, not yet understanding how his words will be twisted against his wife.

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Stacy Schiff describes Salem in 1692 as a place where “one listens more acutely, feels most passionately, and imagines most vividly, where the sacred and the occult thrive.” In smoky, fire-lit homes beneath a “crow black, pitch-black, Bible black” sky, neighbors hallucinated biblical texts into land disputes or mistook a cat at the window for an enemy in disguise. Darkness extended beyond the physical — candlelit interiors, unpaved roads, encroaching woods — to the psychological: a community in which silence could incriminate and averted eyes serve as proof of guilt. In such an atmosphere, paranoia flourished, and the courts rewarded it.

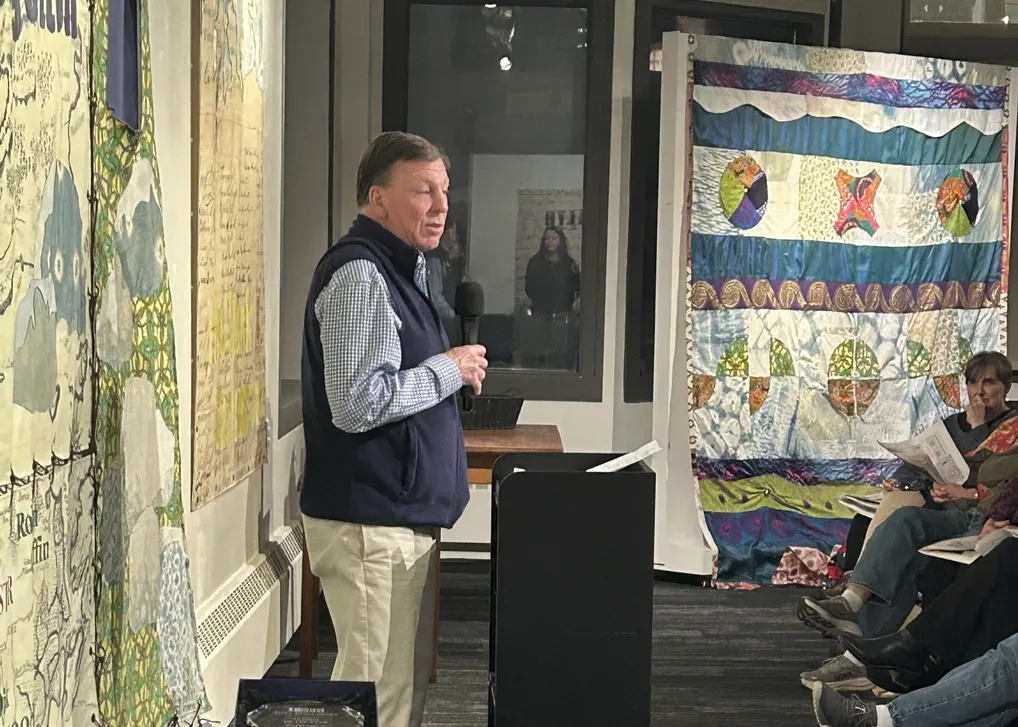

MLT’s production, directed by Trudi Olivetti, immerses audiences in precisely this world. Olivetti has articulated her aim to convey “a strong sense of this community” and its “obsession with order.” Her staging achieves that objective.

The atmosphere was the first success. Greg Mancusi-Ungaro’s lighting sank the stage into shadow as the story darkened, creating unease without distraction. The world on stage felt spare, watchful and ready to collapse, complementing dialogue the cast has clearly lived in to impressive effect. In the courtroom, voices piled on each other until the sound seemed less rehearsed than unleashed. Characters spoke over each other, their words colliding. The rhythm felt natural, like an argument in a crowded kitchen. Then, in sudden pauses, silence landed with real force. In the Proctor household, those pauses spoke louder than any accusation.

The cast brought this texture to life. Jay Gould’s Reverend Hale moved from confident certainty to spiritual collapse. At first his back was straight, his voice firm. By the end he was hunched and pleading, begging prisoners to lie to save themselves. “I come to do the Devil’s work,” Gould said with bitter irony, “I come to counsel Christians they should belie themselves.”

Rebecca Axelrod’s Rebecca Nurse stood as the moral center. She carried calm dignity, and her refusal to bend gave the play its compass. “Let you fear nothing! Another judgment waits us all,” Axelrod delivered with quiet conviction, refusing to confess to save her life. John Macero’s Danforth embodied the rigid voice of authority. His warning that “a person is either with this court or against it” felt familiar and close, not distant history.

Donna Cotterell’s Tituba offered a performance of particular complexity. Her early scene — pressured to confess, then finding terrible power in accusation — revealed the cruel mechanics of Salem’s witch hunt. As the enslaved woman caught between survival and truth, Cotterell showed us someone navigating impossible choices with both vulnerability and cunning.

The Proctors anchored the emotional heart. Jeremy Lupowitz played John Proctor with dignity and restraint. He was not a man of speeches but a man reclaiming a shred of himself. His refusal to sign a false confession came across not as a grand gesture but as a painful necessity. “Because it is my name!” Lupowitz cried, his voice breaking. “Because I cannot have another in my life!“ Theresa Peterson’s Elizabeth Proctor was steady and composed. Her final forgiveness was simple, which made it even more affecting.

The most frightening scene came in the courtroom. Ashley Royer’s Mary Warren tried to withdraw her accusations, only to be engulfed by the others. Led by Shannon Burke’s Abigail Williams, the girls — played by Sophie Leiton Toomey as Mercy Lewis and Niko King-Mahan as Susanna Walcott — turned on her in eerie unison. Their mimicry came in waves — shrieks, gasps, contortions — until the audience itself seemed caught inside the echo. The effect was precise and overwhelming. For a moment, hysteria felt like the most commanding presence on stage. This was also the moment when the Salem court’s reliance on spectral evidence became visible.

Two days after seeing it on opening night, the set and lighting in Act 4 has stayed with me. It was stripped down to bare boards, a barred window and the flicker of a single candle. The light made the scene look like an Old Masters painting, but it also recalled the darkness that Schiff says enveloped the first settlers — a place where faith and fear could not be separated.

Miller characterized writing “The Crucible” as “an act of desperation” during the McCarthy hearings. Olivetti’s production honors that urgency without forcing parallels. It simply shows a community failing itself and lets us draw our own connections to the present.

The production is sold out and runs through Oct. 19 at Marblehead Little Theatre. Check MLT’s website for a waitlist and any last-minute releases.