Table of Contents

In Marblehead, two values run deep: protecting its architectural heritage and advancing climate leadership. But inside Marblehead’s Old and Historic District, those ideals can collide.

In recent years, residents seeking to install solar panels, heat pumps, electric vehicle chargers or energy-efficient windows have encountered denials and costly compromises. In one case, a Front Street homeowner was ordered to remove heat pump equipment after a failed appeal — a vivid example of the hurdles facing those trying to electrify their homes. Another time, a Town Meeting article that would have limited the district commission’s power was withdrawn only after officials pledged to revise the rules.

Some residents have pointed out these conflicts exposed the need for clearer, fairer and more sustainable permitting standards — which new recommendations published in August aim to provide.

“Marblehead Sustainable Heritage: Proposed Recommendations for Clean Energy Retrofits in the Old and Historic Districts” is the product of a two-year effort by MAPC, town officials and residents. It offers practical guidance for solar, heat pumps, EV chargers and efficient windows while preserving the architecture that covers roughly a quarter of town.

Marblehead’s Old Town and Gingerbread Hill districts were created under a 1965 special act and later by bylaw. The Old & Historic Districts Commission — five members plus two alternates appointed by the Select Board — meets the first and third Tuesdays at Abbot Hall and must approve exterior work visible from public ways. Old Town spans the colonial core near Washington, Pleasant and Front streets; Gingerbread Hill centers near Beacon and Harding by Little Harbor — about 800 properties combined. A larger National Register district, listed Jan. 10, 1984, covers about 2,300 acres and 988 properties, with heavy Georgian and Federal stock, more than 200 pre-Revolution houses, Fort Sewall, and two National Historic Landmarks: the Jeremiah Lee Mansion (1960) and the Gen. John Glover House (1972).

But the proposed guideline‘s future remains uncertain. The Old and Historic Districts Commission has not yet adopted the guidelines, sparking debate about whether voluntary recommendations are sufficient or if binding standards that may require Town Meeting intervention are needed to achieve the town’s climate goals.

What the guidelines recommend

The recommendations, obtained by The Independent, establish three core principles for all clean energy retrofits: reversibility, minimal intervention and compatibility with historic character. Upgrades must be removable without damaging historic fabric, visually unobtrusive and modern but subdued rather than mimicking historical features.

For solar panels, the guidelines encourage installation on rear- or side-facing roofs not visible from public ways. Front-facing panels would be allowed only if no feasible alternatives exist and visual impact can be mitigated. Panels must be flush-mounted and low-profile, set back from roof edges.

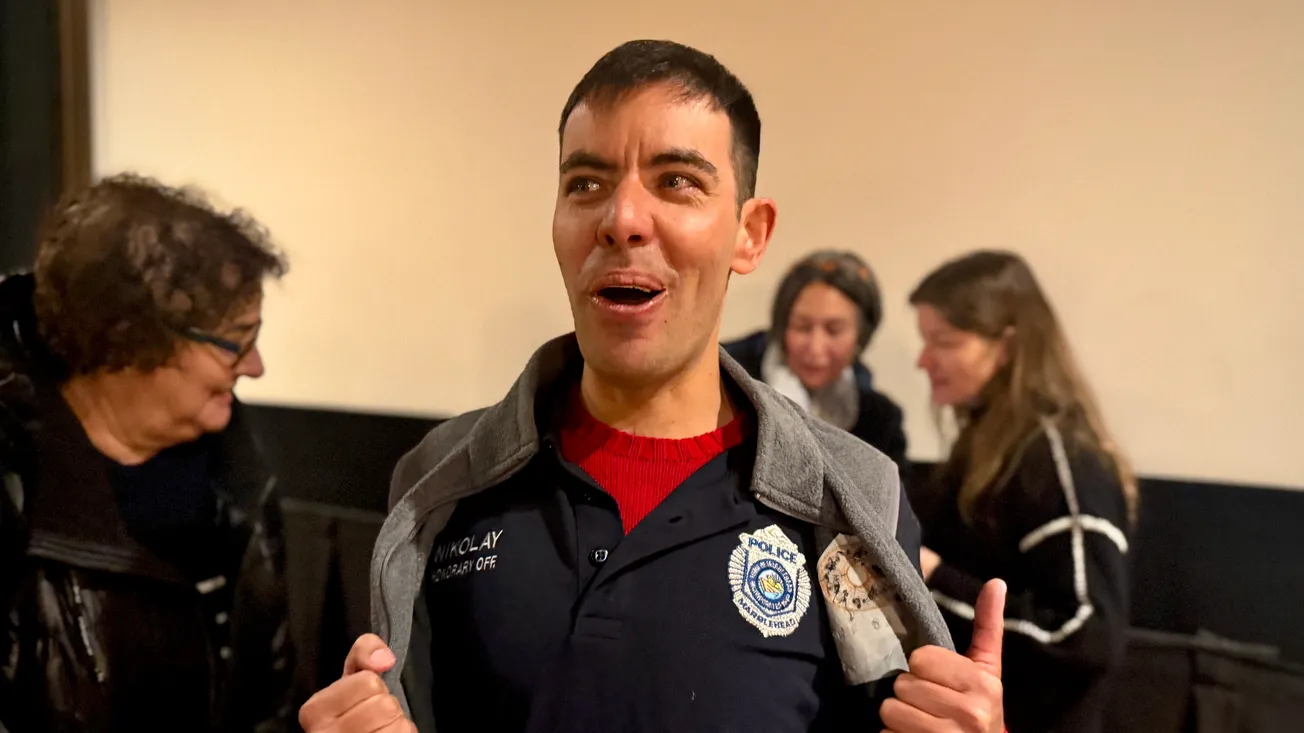

Mark Adams of Sustainable Marblehead said the proposed guidelines remove prohibitive restrictions that have stymied clean energy adoption.

“They remove the outright restrictions such as the language that any visible component of a solar panel system that is visible from any public way is ‘not appropriate to historic buildings,’” Adams wrote in response to The Independent’s questions. “The proposed guidelines also address the specific ways that homeowners can achieve their energy reduction goals and do so in ways that have the least impact on the historic appearance of their property.”

Heat pump condensers should be placed in rear or screened side yards and visually shielded using fencing, landscaping or finishing treatments. Exterior line sets would be allowed if painted to match building exteriors, with conduits running along rooflines or the base of walls. The guidelines suggest using faux downspouts where appropriate.

Current OHDC guidelines state that “exterior line sets will be considered at the discretion of the commission” — language that has frustrated homeowners seeking predictable standards.

“These subjective interpretations have led many residents of the historic district to believe that their ability to get an approval will depend on having a positive prior relationship with the OHDC commissioners,” Adams wrote.

EV chargers should be installed in garages, side yards, rear yards or other low-visibility locations. Wall-mounted units would be permitted on non-street-facing walls with painted conduits matching exterior surfaces.

For windows, repair is preferred over replacement. When replacement is necessary, new windows must closely replicate original designs in grid pattern, sash configuration and glazing. Interior or exterior storm windows are favored, with wood materials preferred.

How the town got here

The initiative stems from Marblehead’s commitment to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2040, as outlined in the town’s Net Zero Roadmap. After years of case-by-case decisions with the OHDC, Marblehead received a $25,000 MAPC grant — applied for by former town planner Becky Cutting — in May 2024 and partnered with the regional planning agency to develop a new framework.

The process included walking tours in Marblehead and Salem, public forums, presentations from preservation experts at Newport Restoration Foundation and Historic New England and collaboration with Green Marblehead Implementation Committee members. MAPC compared OHDC guidelines with national preservation standards and policies from Nantucket, Concord and Salem.

Adams said MAPC “did a very thorough job” comparing guidelines and found that “in many areas, the OHDC guidelines are far out of alignment with best practices and need to be updated.”

The Independent reached out to Charles Hibbard, OHDC chair, for comment but did not receive a response by publication time.

Marblehead Green Implementation Conmittee member Eileen Mathieu said her biggest goal is “to get those guidelines adopted” so the town can move toward its net-zero emissions target.

“If OHDC continues to insist on doing things the way they’re doing, that really does make it harder,” Mathieu said. “Every year, if someone needs a new heating system and OHDC is too inflexible, then another 10 people go and get traditional gas burners instead of getting heat pumps.”

At the GMIC’s Oct. 9 meeting, Mathieu pushed for the committee to formally recommend adoption to the Select Board, arguing that the committee’s endorsement would give the guidelines additional weight and show the town’s climate advocates stand behind the proposals. That may appear on its next meeting’s agenda.

Andrew Petty, director of public health and Green Marblehead member, expressed desire for more definitive rules.

“I’m concerned with the term guidelines. I really like to see more bylaws that are more definitive, rather than kind of loose guidelines or whatever,” Petty said during the meeting. “I want homeowners to understand that you are buying a piece of treasure in Marblehead, and this is what you’re allowed to do.”

The path forward

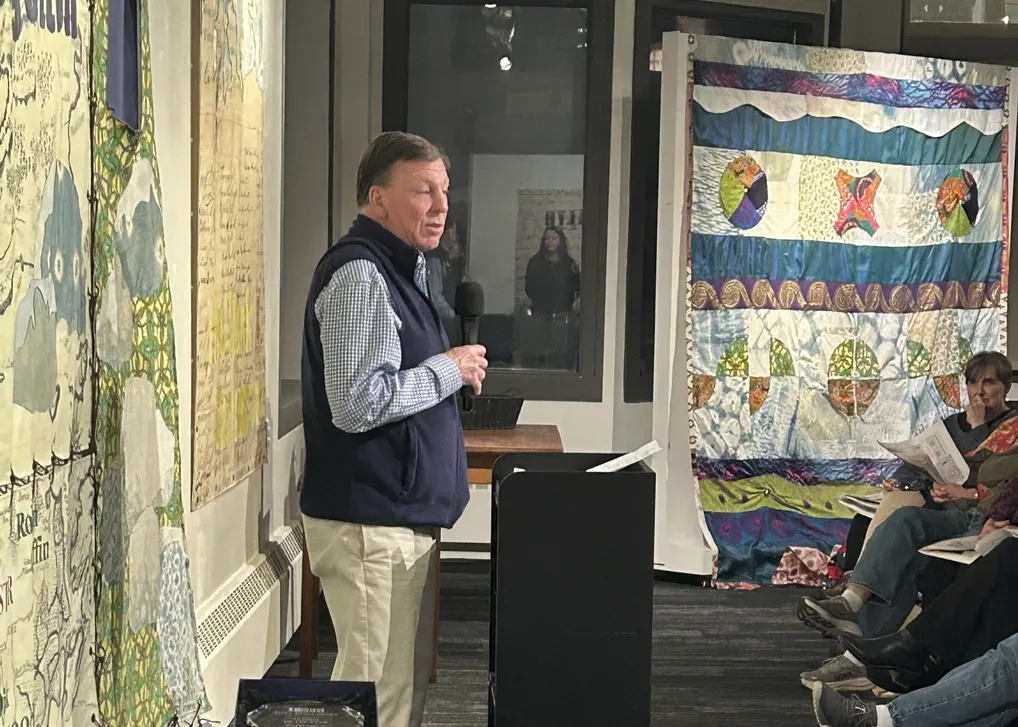

The OHDC has not yet adopted the guidelines, which remain voluntary recommendations. Town Administrator Thatcher Kezer has suggested a diplomatic approach, with a presentation to the Select Board followed by the board asking OHDC to consider adoption.

However, Adams said OHDC “has complete authority to update their guidelines, and I would urge the commissioners to adopt the MAPC proposed guidelines as soon as possible.”

He added that if the commission does not act, “the Select Board needs to question the OHDC commissioners as to why they would ignore the recommendations of the MAPC report that the Select Board commissioned and hold OHDC accountable.”

Adams closed with an urgent appeal about climate threats facing the coastal community.

“We are a low lying community that will be amongst the first to experience the ravishes of climate change and rising oceans,” he wrote. “If we don’t do our part to address this threat, then we won’t have historic properties worth preserving.”