Table of Contents

Get the latest from The Marblehead Independent delivered straight to your inbox.

Sometimes a story finds you, and you can’t let it go until you tell it.

In early 2024, while mindlessly thumbing through my Facebook newsfeed — a habit as automatic as brushing my teeth — I encountered her: a young woman pushing a bicycle, paused before a vine-draped house on a winding Marblehead street, captured in a black-and-white photograph. Her blouse was sleeveless, her smile effortless and radiant with light. The air appeared warm, her posture utterly unguarded.

For a moment, the picture is pure Americana — before you notice the caption: “Sylvia Plath, Marblehead, 1951.” She seemed to belong entirely to that moment — and yet not at all. Knowing her ending makes every smile before a kind of fiction.

The photo piqued my curiosity enough to call Pam Peterson, chair of the Marblehead Historical Commission. She confirmed that Plath had, in fact, spent a summer nannying for a Swampscott family.

I felt compelled to delve deeper. I visited the Salem Public Library and checked out “The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath” alongside a volume of her collected poems. As I opened the latter — purely by chance, amid hundreds of entries — it fell directly to “The Babysitters,” a moment of uncanny serendipity that I swear — hand to heart — was unprompted. There, rendered in stark black and white, unfolded a vivid, bittersweet poem chronicling her three-month tenure caring for children in Marblehead and Swampscott: the lively youngsters, the stately houses, the oppressive heat and an undercurrent of melancholy.

I found a name — Mayo — and, on Patriot Properties, an address. I left a message, got a call back. Three months later I found myself in a sunlit Ridge Road living room in Marblehead, sitting across from the three siblings — Freddie, Pinny, Joie Mayo — whom Plath cared for over seven decades earlier.

Eyelid kisses and bedtime pinches

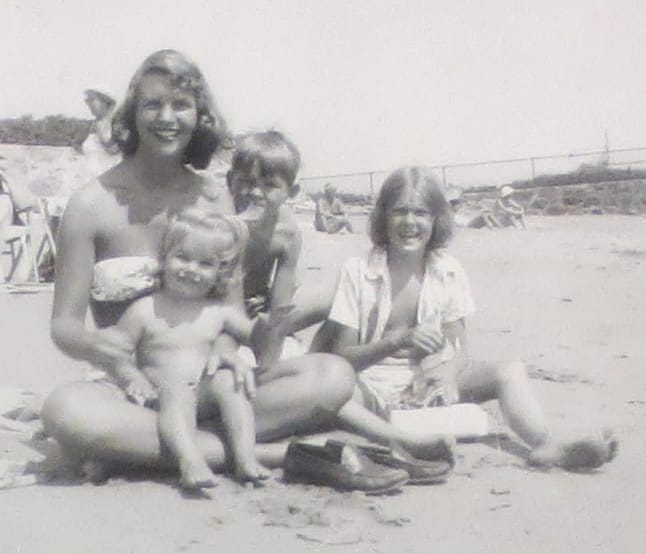

When asked what they remembered, the Mayo siblings found it challenging to reconstruct memories of the 18-year-old Smith College student who resided with them for a single summer in 1951. “I can’t offer anything — she was just one of the babysitters,” Pinny stated matter-of-factly. “We had them every summer,” Joie concurred, nodding, with no distinct recollections of Sylvia Plath’s voice or presence lingering in their minds.

This lack of clarity is understandable. At the ages of seven, four and two, they were too young to form lasting impressions of what they called the live-in “mother’s helper” who arrived at their family’s former home on Beach Bluff Avenue in Swampscott — a once-grand, multi-story mansion constructed by their great-grandparents, subsequently shortened in height during World War II, yet remaining an imposing, white structure with expansive porches and a sea-overlooking yard.

In contrast, Plath — the American author who would later publish “The Bell Jar” — detailed the children with luminous detail. As documented in her unabridged journals, she portrayed their individual quirks with a blend of tenderness and exacting precision.

I read aloud from her journals — often written in second person as if she were observing herself — and the room filled with laughter and recognition.

Here was Joie, 2:

“[Joie] fussed and cried as you took the pants off her plump little body … Docilely, she let you put her in the crib, where you bent over her for a while, letting her pinch your nose and cheeks.”

Joie laughed at the image of herself pinching Plath’s nose. She had no memory of it, but there it was, inked forever.

Here was Pinny, 4:

“You gave her a front seat up the stairs and her pale blue party dress, white shoes and blonde hair … a little girl, a bit unsure of herself because of the love lavished on the baby and the domineering mastery of talkative Freddie.”

Pinny nodded. “That’s me,” she said — the husky voice, the middle-child insecurities.

And then Freddie, 7:

“Freddie was last and by far the most interesting and amusing: a talkative Kewpie-doll-faced boy of seven with the Beau Brummel taste for socks and jerseys that matched. Tonight, after a tale about a crooked mouse, he responded to ‘Going to give me a goodnight hug?’ I responded to my ritual good-night hug with a kiss on one eyelid. ‘Now I have to kiss the other eye,’ he said.”

The room erupted. “Bow ties!” Freddie laughed. “She nailed me.”

Other entries captured the same blend of his entitlement and sweetness. “I like being little and staying up,” Freddie told Plath. “Because then big people have to wait on me.” She recorded how he offered her sips of iced tea, “as if you were a girl dying of thirst,” as she played the piano.

Until I’d read them aloud, the Mayo siblings had no idea such passages existed, or that they’d been preserved in the notebooks of one of the 20th century’s most famous poets.

Overwhelmed by three little kids

Plath — whose widowed mother Aurelia was an associate professor at Boston University — suddenly found herself immersed in a very different world. Born in Jamaica Plain, Plath was eight when her father died, prompting her mother to move the family to Winthrop.

The Mayo siblings described their own family background: their father, Dr. Frederic Mayo, was a soft-spoken internist; their mother, Barbara Blodgett Mayo, a sporty, socially attuned woman with deep New England roots. The Mayos belonged to a yacht and beach club — the kind of lineage where you didn’t just summer on the North Shore; you inherited it.

Plath, a rising sophomore at Smith College, got the summer job through the siblings’ maternal grandmother, Ruth Payne Blodgett. Blodgett, a 1904 Smith graduate, regularly hired students — her way of paying it forward.

“She helped find summer jobs for Smith girls,” Freddie said. “That was the tradition.” The family says she may have even helped cover some of Plath’s tuition.

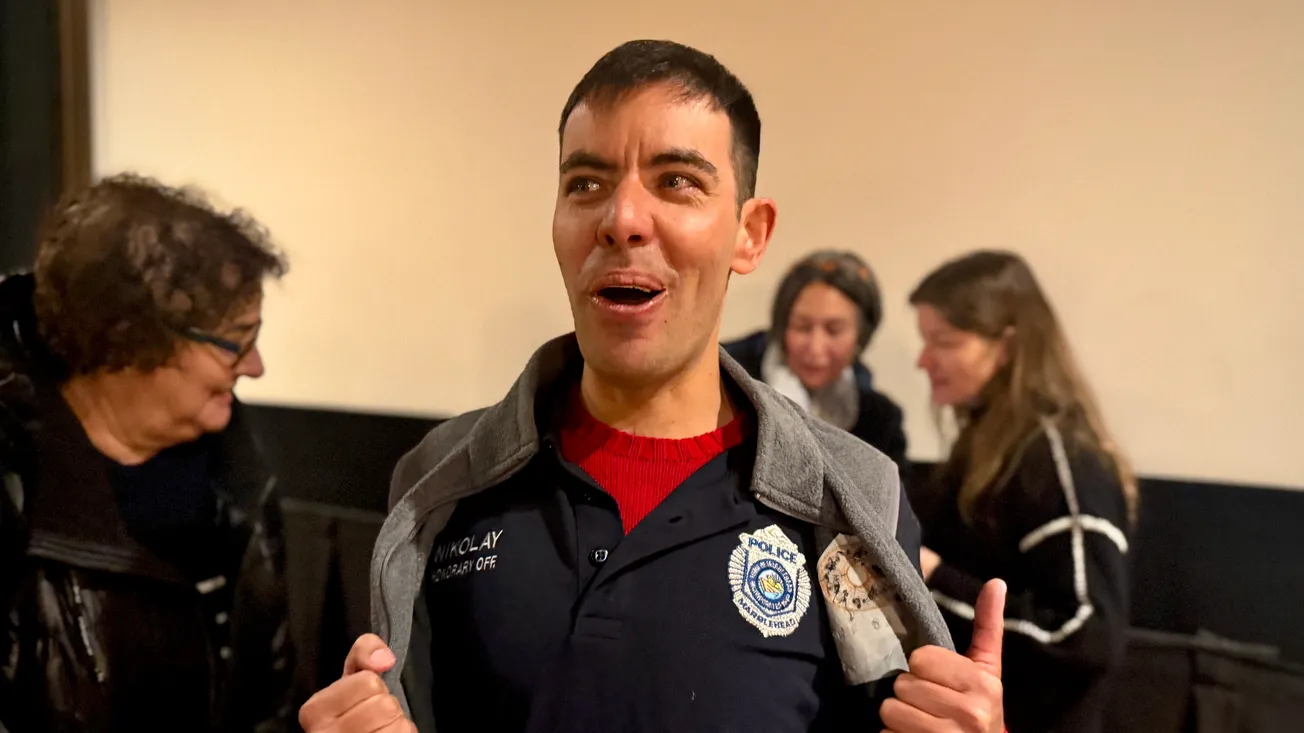

Plath’s friend and classmate, Marcia Brown, joined that summer as a second “mother’s helper” — a companion on rare days off — for a Marblehead family. One photo shows them together, resting with the family dog at a rocky Marblehead beach — two Smith students briefly at ease.

Freddie noted that Plath “was overwhelmed with the task of three little kids,” and “wasn’t used to being on all day,” suggesting a class and emotional divide.

Even as she struggled, she observed the patterned china, the way the parents read after lunch — he with medical journals, she with novels — before drifting into sleep.

“Our parents were happy,” Pinny said simply. “They always traveled together.” Freddie agreed: “There was a rhythm to them, and Sylvia seems to have picked up on that.”

What often felt suffocating in her own life seemed, in them, to offer stability and quiet affection.

“She probably wasn’t used to seeing that,” Pinny said.

Barbara, the siblings said, didn’t love it when Plath shut herself away with a notebook. “To her, if the kids were asleep, you should be folding laundry — not scribbling,” Pinny said. The quiet enforcement of “woman’s work” left Plath feeling her identity slip away. “God, who am I?” she wrote. “I sit …without identity: faceless.” She feared “marriage and children” might “swallow up [her] desires to express [herself].”

Plath often described that summer’s labor as demoralizing, but the work of caring for children is anything but. It humbles, strips away pretension and demands attentiveness — qualities she came to glimpse by the end. What once felt like drudgery hardened into a rite of passage, clarifying her resolve to write harder, hold fast to her identity and be more than convention allowed.

Reading those pages now, with the distance of age, it’s hard not to admire her stamina: at 18, she managed the duties of a household while also rising early to revise her poems. She was never a poet of sudden inspiration but a worker who treated writing like a second shift, unwilling to let her voice be dissolved into service or silence.

Marblehead as refuge, respite

For all the exhaustion and grind, Marblehead itself became a refuge for Plath. In her journal, she described a rain-soaked day in town with searing detail:

“The most vital spot in the world for me was today in the rain, in an old gravel parking lot in Marblehead, where, beyond a rusty shack, was the harbor, and the neat upright forest of masts. Houses were close together, and yellow flowers were growing in the wild grass … Somehow, sitting there in the light blue Plymouth, your grandmother beside you, your mother in back, you cried with love for them because they were your own people, your own kind … This hour was yours, to steer through the narrow crooked streets, to sit and talk and watch the rain, to absorb the love of kin, of rain, of the masts of sloops and schooners. And when you swung the car into reverse, roaring out, back to your job, you felt whole and human once again.”

That passage, written by an 18-year-old, is one of the most lyrical entries in her journals from that summer.

She also chronicled a trip to Children’s Island, the rocky island where she and Brown rowed on their day off. In “The Babysitters,” the island becomes both escape and ghost:

“So we bobbed out to the island. It was deserted

A gallery of creaking porches and still interiors,

Stopped and awful as a photograph of somebody laughing

But ten years dead.”

That memory of escape would surface again years later. Joie recalled a moment at the hair salon: “When mom was having her hair done — which she did once a week — someone came over and said, ‘Bobby, I think this is your family.’ She read The New Yorker. She was horrified and almost wanted to go buy all the magazines so nobody could read it.”

She was talking about “The Babysitters,” which The New Yorker published posthumously on March 6, 1971, in a group of Plath’s poems with the headline “Six Poems.” Plath transformed that summer experience into art. The poem, lyrical and laced with ambivalence, drew directly from her time in Swampscott and Marblehead: the “plump little baby,” the “sporty wife and her doctor husband,” the guest cottages and green-shaded lamps, the cook with a nervous eye, the row to Children’s Island.

For the Mayos, its publication was jarring — their ordinary domestic life reframed in poetic terms, their private routines turned into literature.

Flowers in her hair

For the siblings to hear, I brought along a 1961 BBC radio recording of Plath’s voice. In it, she’s not recalling Massachusetts but describing what drew her away from it to live in Britain: the moody weather, the seaside villages, the butcher shops with their unwrapped slabs of meat and what she called the “quiet eccentricity” of the English. She’s joined by her husband, poet Ted Hughes, as they reflect on their decision to settle in the countryside — two writers trying to make art and raise a child in a place that, in her words, “seemed a great deal more hospitable to a couple of artists … who at the same time [wanted to] lead a very normal and rather placid family life.”

Still, she never let go of the coastline. “I was brought up on the northern coast of Massachusetts,” she says in the same interview. “And my whole childhood was spent on the ocean.” She remembered hurricanes, sharks in the garden, salt on her skin. “The image of the sea has been with me ever since,” she added. In England, she liked knowing no place was more than 70 miles from the shore.

After the recording ended, the Mayos were struck by the precision of her diction.

“If you’re a poet and you really want to be a poet, you value every word and the choice of word,” Freddie said.

He laughed, too, at people’s reactions when he mentions his Plath connection.

“Whenever I tell friends that Sylvia Plath was our babysitter, the reaction is always the same: You’re kidding. Sylvia Plath?” he said. “They’re stunned. Even jealous. To them she isn’t just a poet — she’s a feminist icon.”

Where their memories falter, her journals blaze. By the time the nanny stint ends, she laments leaving the three children. But make no mistake, she was overwhelmed that summer — there is no question. She cried in the kitchen her first day, blistered her fingers on the iron, wrote “spitefully” in her diary about babies that depressed her. She resented being “only the maid.” And yet, alongside the resentment and ambivalence, she evolved and recorded these tender observations of the children.

In her journal, one entry describes the children putting flowers in her hair.

“I closed my eyes to feel more keenly the lovely delicate-child-hands, gently tucking flower after flower into my curls,” she wrote, “and all my hurts were smoothed away.”