Table of Contents

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered directly your inbox — stories that show up for accountability, for community life and with a long memory. Subscribe free →

On summer mornings at the Lead Mills Conservation Area, four rising high school juniors could be found waist-deep in wildflowers and invasive vines, armed with pruning shears and an irrigation system engineered from garden hoses.

The work was hot, dirty and often prickly. But for Evelina Beletsky, Naomi Goodwin, Julia Betz and John Burke, the Marblehead Conservancy’s first paid summer interns at the waterfront property, the experience transformed how they see the landscape around them.

“I think it helped me understand the importance of things beyond schoolwork and academics — the hands-on part, and how it impacts the community as a whole,” Goodwin said. “We had multiple people walk by from our community saying, ‘Your work is so amazing, I love what you’re doing, it’s making such an impact.’”

The four teenagers spent their summer helping restore the 4.5-acre site at the mouth of the Forest River into a pollinator meadow. The property, purchased jointly by Salem and Marblehead in 2012, once hosted the Forest River Lead Works, a 19th-century manufacturing complex that produced white lead paint and Civil War ammunition until fire destroyed it in 1968.

Now the conservancy’s Wildflower Committee is gradually converting the former industrial brownfield into a refuge for declining native bee and butterfly species. The interns became crucial partners in that effort.

From classroom to conservation

Beletsky, Goodwin and Betz learned about the opportunity when conservancy members visited their National Green School Society club at Marblehead High School. Burke, who attends St. John’s Prep, heard about it through his water polo team. All four jumped at the chance for paid work with an environmental focus.

Their major project tackled an area conservancy members call “shrub area one,” which had become choked with oriental bittersweet, an aggressive invasive vine.

“We worked on this project where we worked on cutting the bittersweet vines that were behind one of our like sections,” Beletsky said. What organizers expected to take weeks, the crew finished in days.

Stories like this one are made possible by readers who see journalism as part of community stewardship — the same hands-on spirit that keeps native wildflowers alive at Lead Mills. Join them in sustaining independent reporting for 01945. Support The Independent →

They also removed Queen Anne’s lace, the delicate white wildflower beloved by gardeners but classified as invasive at Lead Mills because it crowds out native plants that co-evolved with local pollinators. In its place, they transplanted native species including milkweed for monarch butterflies, goldenrod for native bees and white aster.

The restoration follows research from the Gegear Lab at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, which identifies plants critical for bumblebee species that have declined more than 90% in some regions over three decades.

Hands-on learning

Heidi Rubin, school nurse at St. John’s Prep and a Wildflower Committee member, coordinated the interns’ work. She said the crew’s contribution went beyond the physical labor.

“We couldn’t have done half the projects that we did this summer without the help of the crew,” Rubin said, smiling over a Zoom call with the four interns.

The interns worked flexible schedules, sometimes putting in just two hours to water plants, other weeks spending full days removing invasives as a group. The work connected them to ecological processes many had never considered.

“I enjoyed seeing all the different pollinators that usually you don’t see around here due to it being more like a suburban area that is mostly just houses with a lot of the like nature’s kind of just replaced, in a way? Well, there is just all natural. And I’ve seen a lot of things there. I’ve not seen in a while,” Burke said.

For Burke, the site became an outdoor laboratory. For others, it meant confronting childhood fears.

“This job helped me learn new skills like gardening and maintaining plants,” Beletsky said. “As a girl who grew up staying away from insects, I felt less afraid and more comfortable around them.”

Building stewardship

Betz had a similar transformation. “Before doing this job, I hadn’t really thought much about animals or bugs,” she said. “But I’ve seen so many dragonflies and pollinators, and it makes me so happy that we’re helping increase them through this project.”

The experience also sharpened their eye for invasive species throughout the region.

“I think it helped me realize how many invasive plants are around that people just assume are normal,” Goodwin said. “They look pretty, so most people don’t realize they’re actually invasive and harming native species.”

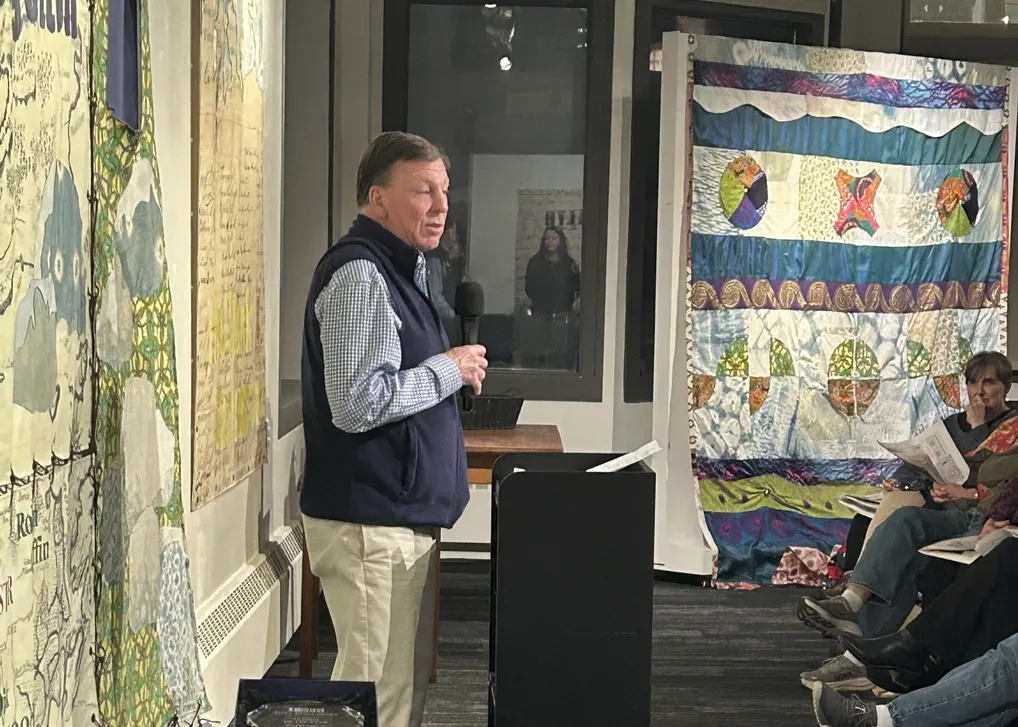

Bob French, longtime conservancy member and its president, said the internship program addresses a critical need for the all-volunteer organization.

“I’m very, very happy that this particular group was working over there. They did a fine job. Set a great example for others,” French said. “Because we could use, we could use more young people involved.”

The Lead Mills meadow, visible from Route 114 at Marblehead’s gateway, now displays waves of native wildflowers where industrial waste once contaminated the soil. For the four teenagers who spent their summer there, it represents something more personal: proof that landscapes can heal and that their generation has a role in that restoration.